Educational practices in art museums don’t often make the pages of major newspapers, so I was pleasantly surprised to see this article, “From Show and Look to Show and Teach,” in the New York Times a few months ago (see also Lindsay Smilow’s earlier response to this NYT article). After a cursory glance, I assumed it would detail educational activities as part of an ongoing commitment to fostering free-choice or constructivist learning experiences in some of the most well-known museums on the planet.

As I read, two assumptions of the author began to take shape:

- “education” in museums is equated primarily with engaging in processes of art making; furthermore, museum guests expect such offerings under the auspices of “participatory events;” and

- the locations of education programs provide significant but conflicting messages.

On one hand, the writer cites the director of the Whitney asserting that “education is part and parcel of what we do” after explaining that the physical space for educational activities (presumably at other institutions) is often physically isolated. Shortly thereafter, the author lauded the rather unique Whitney Studio, a “pop-up” center for education at the Whitney that is not only isolated, it is separate from the building altogether. It seems metaphorically significant in this instance that this temporary space is made from enormous shipping containers.

These assumptions prompted me to reflect on my own thoughts about what constitutes education in museums, and where that education should occur. As a graduate student in the mid-1990s I was fully ingratiated in the paradigm of Discipline-Based Art Education, in which aesthetics, art history, art production, and art criticism are considered basic subject areas from which to derive content for art education—while art production for me has always been one way to come to a better understanding of art, the conversations that may be engendered in gallery and other spaces have always been far more intriguing and significant in my own educational practices.

I am certainly not the first person to reckon with the importance of art making as part of an overall educational endeavor. My colleague and friend, Professor B. Stephen Carpenter, made an interesting comment during a panel presentation on reconceptualizing curriculum at the 2012 NAEA convention in New York City. He questioned, ever so briefly, whether or not the act of art making is, in fact, the primary goal/foundation of every model of art education, though his question specifically focused on eco-environmental curriculum. At the time, I thought… if it is primary, then where does that leave the myriad other discourses that surround art education and art museum education? What happens when we as professional educators privilege a particular kind of knowing over all other ways of relating to objects in the museum, particularly when few people excel at those skills, especially as they are presented in very short classes?

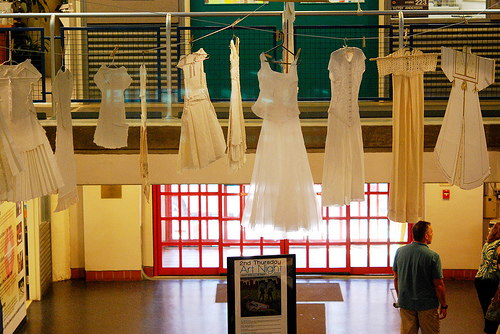

The article featured other examples of art-making-as-education in spaces outside the museum, such as Open Field, a grassy space next to the Walker Art Center, and several digital spaces, including online art production classes offered by the Museum of Modern Art. Art museum education has long been relegated to basements and other hidden or cordoned-off areas of the museum, and I pause to wonder what messages are being transmitted when learning is offered outside the physical space of the museum.

Does this practice reify the notion that education is a by-product of the more serious business of being in the galleries? Or is it simply a practical response to a space issue for educators who are increasingly offering educational opportunities that are responsive to their particular learning communities, collections, and spaces?

If one considers art making to be an important exercise with which to engage in order to understand art, a separate space is necessary for obvious reasons, as art can be (and should be) messy. If not, then the what and the where of art museum education is an important and evolving conversation.

I invite you to add your own thoughts and perspectives below, so we can continue to engage in productive exchange about these ideas that are core to our profession.