Written by Amanda Tobin

Earlier this month, I had the honor of leading a gallery teaching demonstration at the Metropolitan Museum of Art for a group of colleagues during the NAEA Pre-Conference for Museum Education. I had answered a call from the Museum Education Division looking for educators to showcase best practices that can be applied to using gallery teaching towards racial equity.

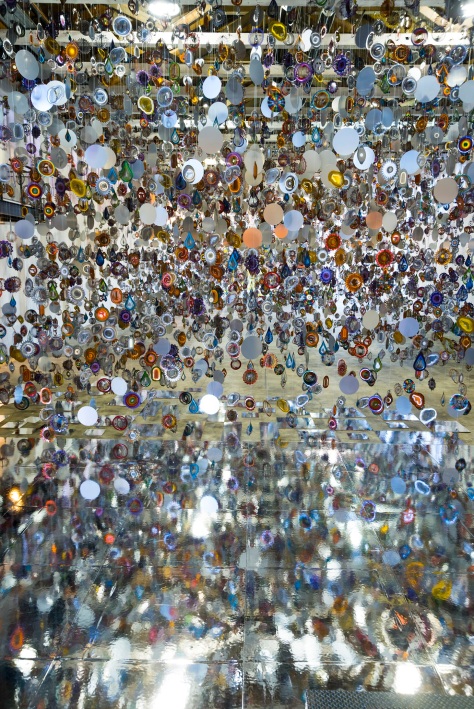

At MASS MoCA, we have been grappling with these questions in our current exhibition, Nick Cave: Until. An immersive, football-field-sized installation, Until was a departure in scale for Cave, who is well known for his human-sized Soundsuits. In aesthetic and in mission, however, Until is very Nick Cave: tchotchkes, sparkles, and wonder are expertly woven together in service of an urgent social mission around violence and racism.

Until is Cave’s response to the highly fraught instances of police violence towards communities of color. The title of the exhibition is a play on the phrase “innocent until proven guilty,” or, Cave suggests, “guilty until proven innocent,” drawing attention to the different ways the criminal justice system has different standards for different communities. As visitors progress throughout the installation, they are lead through an experience of awe to one of discomfort and vulnerability as the layers around violence and racism reveal themselves.

No easy task for an Education Department. But we knew that Until would provide an unparalleled opportunity to engage new and existing audiences with these questions in ways that could provoke thought, dialogue, and ultimately, action in support of racial justice.

In designing our tours of Until, we relied on our tried-and-true three-pronged pedagogical approach at MASS MoCA: guided conversations, art-making, and mindfulness. That last piece is what I brought to NAEA. In my teaching practice at MASS MoCA, I’ve seen how mindfulness practices heighten students’ observations, building metacognitive skills and increasing focus and awareness. In Until, a walking meditation through Cave’s field of spinners has helped students realize their physical, bodily responses to moving through the space — which has been critical in developing attention to the images of guns and bullets woven throughout the field of spinners as well as to the anxiety, dizziness, and even fear such a space provokes. This is counterintuitive to many visitors, whose first response is typically “oohs” and “ahhs”; that something so beautiful could be so discomfiting is part of Cave’s intention, and mindfulness helps visitors make that connection.

At the Met, however, there was no large field of spinners within which to lead a guided walking meditation. Instead, I led a discussion around John Steuart Curry’s 1939 painting, John Brown, inviting my colleagues to explore gut reactions to the figures in the painting: the (anti-)hero abolitionist, John Brown, and an unnamed slave, easy to overlook in the lower left hand side of the painting. After collecting one-word reactions to each of the figures, I led a visual analysis of the image, to encourage the group to explore what visual elements (scale, shading, expression) had contributed to their first reactions. I chose not to disclose who the figures were at the beginning, but introduced John Brown and the anonymous Black man halfway through, to see what impact the identifying information had on our collective analysis.

Finally, I led the group in a mindfulness exercise around “carrots and peas,” adapted from Mindfulness & Acceptance in Multicultural Competency: A Contextual Approach to Sociocultural Diversity in Theory & Practice (edited by Akihiko Masuda).[1] Though intended for cognitive behavior therapists, the exercise has worked well in arts educative experiences I’ve led at MASS MoCA. As mindfulness practice goes, it’s more metacognitive than meditative, building consciousness of immediate assessments that often go unexamined or unacknowledged.

In essence, “carrots and peas” goes like this:

- Tell the group that you will ask a simple question (e.g., “I’m going to the grocery store. What should I buy?”) and providing an answer (“Carrots and peas”).

- Repeat the question with group providing the answer at least five times.

- Then ask them to answer the question one more time with a different answer.

More often than not, participants struggle to provide an answer that was not “carrots and peas.” Sometimes visitors blurt out “carrots and—” before cutting themselves off; most often there is simply a pause as their brains struggle to rewrite the script. After only five repetitions, the pattern is in place; one participant remarked that she “forgot what else you could even buy in a grocery store.” Another example of this thought pattern is to fill in the blank: “You can’t judge a book by: ____.” How hard is it to not think “its cover”?

The goal in using this exercise is to help visitors explore the implications for real-world or arts-based situations in which our actions may be informed by unconscious stereotypes. With the group last week, we followed up this exercise with a great conversation around John Brown and the unnamed Black man in Curry’s painting. We explored how Curry draws our visual attention to Brown first, and how “carrots and peas” can help us to instead learn to look for the other figure who is quite literally marginalized on the canvas, extrapolating into real-world scenarios regarding representation and power.

While no brief museum experience can upend years of cultural socialization, “carrots and peas” can lay a foundation for building a better awareness of one’s implicit biases. Through this call-and-response exercise, participants are shown how easily our minds build simplified patterns of thought — whether innocuous, as in carrots and peas, or harmful, as in stereotypes of Blackness and criminality — and how an awareness of this tendency can lead to a disruption of behavior that is based on unquestioned habits. By acknowledging these habits of thought, participants can identify whether or not these patterns align with their core values and can begin checking implicit biases to ensure they correct behavior that is detrimental to our humanity.

* * *

About the Author

AMANDA TOBIN is the K-12 Education Manager at MASS MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts, where she has developed school engagement programs around social justice since 2014. She holds a B.A. in Art History and East Asian Studies from Oberlin College and an M.Ed. in Arts in Education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She is also an avid farm share member and crafter, needle felting small succulent plants after having no luck keeping real ones alive. She can be reached at atobin@massmoca.org.

* * *

[1] Lillis, J. & Levin, M. (2014). Acceptance and mindfulness for undermining prejudice. In A. Masuda (Ed.), Mindfulness and acceptance in multicultural competency (181-196). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc. p. 188.

Great article! Sounds like a really valuable method of exposing and thinking through implicit bias.

Did you know that the Journal of Museum Education has an open call for articles on ideas like these? You might want to check it out here: http://museumeducation.info/jme/call

Thanks for your feedback, and for pointing that out! Much appreciated!

This article is very interesting and thought-provoking.

I participated in the session you gave and have thought a lot about it since. I wonder how we as museum educators might adopt new practices, so that we are not re-affirming the mental habits that keep that black figure in the painting anonymous and peripheral. Given the conference’s keynote “Breaking the Silence of Racism in Museums” this task takes on new urgency. For example, what if we used the carrots and peas exercise as a warm-up before the visual inquiry, connect it to our institutional and national history of racism, exclusion and oppression, and state an intention to subvert that history in our inquiry together.

Often, sharing information is another opportunity for subversion as well. What if, instead of sharing information about the two white men, the artist and the abolitionist, we had shared information about the Black experience of the raid and its aftermath (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2941.html and http://www.blackpast.org/aah/anderson-osborne-p-1830-1872), or about the Black-led rebellions in Haiti that preceded this and are said to have inspired Brown? It might that have opened up the conversation to bring agency and voice to the Black figure, rather than further oppression by having the black figure remain peripheral.