Written by Danielle Carter

Participation in the museum sector has become a buzzword, used at such a high frequency that it can oftentimes be misunderstood amongst museum professionals or, in some cases, so that it becomes meaningless from overuse. When talking about participation, it is essential to discuss the theoretical aspects of what participation is, what it can be and/or what it should be, as well as how these participatory practices are grounded in practice; in other words, what are the theories of participation and how are these theories employed in museum practice?

Nina Simon is our go-to model for what participation in the museum is and/or what it should look like. While her blogs and her writing are a great resource, it is only natural that multiple voices, views, and opinions on this topic exist and — if you will allow me to particularly corny — they should be allowed to participate in the conversation too.

The Maastricht Centre for Arts and Culture, Conservation and Heritage hosted a conference in March 2017 with just that particular goal in mind: practitioners and researchers from various backgrounds in arts and culture gathered to discuss the multiple meanings and practices of participation within the arts and heritage sector.

In this post, I’ll discuss some of the outcomes and more significant thoughts and discussions that occurred during the conference as well as their relevance to museums and learning in the museum space.

Why participation?

Participation seems like the natural next step in the evolution of museums away from the uni-directional, aristocratic collectors’ cabinets of curiosities of yore, right?

There are many reasons to integrate participation into the institution of the museum — if you are low on funds, volunteers are great; if you are trying to reach a new community, allowing the voices of that community into your institution is the best way to reach them (see again: Nina Simon’s The Art of Relevance); if you want your visitors to engage in the museum content in a less uni-directional, top-down manner, participatory practices can be the key. Just from the examples listed above, it becomes obvious that participation can be defined in many different ways: volunteering can be participation, encouraging visitors to create their own meaning and perhaps contribute that to an exhibition can be participation, etc.

Overall, participation involves parties from outside of the museum institution, often in a way that invites them to contribute in a meaningful way — meaning that they contribute in a way that has some kind of effect or impact either on their experience of the museum, on visitors around them, or on the institution as a whole.

How should participation be integrated into museums?

For most of us, we see participation only as a possibility in the outreach, marketing, or education departments. The curators will remain the curators — experts in their fields — but educators are the ones who must create this (illusion of?) participation within the museum space. Although I will admit that this is a great step for many institutions, this is definitely and obviously short of institutional change.

Lena Porsmo Stoveland’s presentation on her experience as a student curator wonderfully reflected the various levels at which participation can take place. She argued in her presentation that the life of the object was a participatory one: a. the object of her discussion was an altarpiece created by several craftsmen, b. the altarpiece was used by church members in Sweden, c. the altarpiece became a museum object, and d. the altarpiece was restored and conserved by a collaboration of Finnish, Sweden, and Norwegian university students.

Building on this in his presentation on “the uncomfortable conversation between artworks and communities,” Dr. Jeroen Boomgaard formulated the identity-forming interaction between artworks and viewers. In other words, communities attribute meaning to artworks (despite the intent of the artist and/or commissioner) which results in an evolving object biography. Rogier Brom later expanded on this with his case study of a clothespin-shaped sculpture located in the courtyard of a school: the sculpture is no longer referred to by its name but by “wasknijper” (clothespin in Dutch); it was once located near the entrance of the school but, after a renovation, it is now located behind the school; and there was once a gardener that hated the sculpture so much that he let the bushes grow wild around so as to consume the entire sculpture, hiding it from view completely.

Sure, the interaction between public artworks and communities differs from that between museum objects and museum visitors, but these interactions have a familiar ring to them: although museum objects remain relatively static in their position within the museum space, the meanings attached to them are still in flux, dependent upon the visitors in the gallery or the way that the exhibitions are arranged at the time. In a participatory museum, the meanings attached to museum objects should always be in flux; rather than the museum telling visitors the significance of the object, visitors should be encouraged to connect with the object on their own terms. As Boomgaard and Brom elaborated, this process is inevitable in the case of public art, because an institution typically does not mediate the interactions between the public and the art.

Participatory practices and learning in museums

Although it was great fun to absorb new information and perspectives about different levels and variations of participation within arts and heritage, this is a museum education/learning blog after all and I am a museum educator and researcher, so I must return to participation and learning.

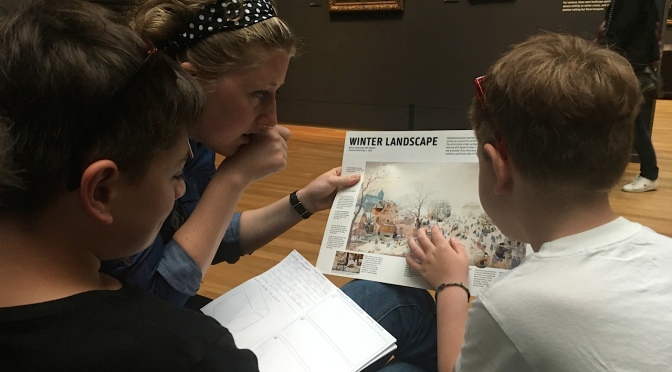

One of the last panels of the conference focused on participation and learning in arts and culture, of which the three presenters focused on participation and learning in the museum setting: Stefanie Metsemakers presented on the learning experience of adolescent volunteers in art museums, Emilie Sitzia focused on the learning potential of participatory practices through the lens of narrative theory, and I discussed the potential for the integration of play in the museum space to instigate participation and, thus, learning.

By inviting visitors to contribute to the museum in a variety of ways, participation aligns with affect theory as well as Falk and Dierking’s Contextual Model of Learning (as well as narrative, as Sitzia focused on her presentation — but that is a big enough topic for another blog post… or dissertation).

In essence, participatory practices in the museum setting validate visitors’ contributions, feelings, thoughts, reactions, and emotions, which, in turn, confirms the significance of visitors’ affective experiences. For example, by asking visitors questions or by asking them to participate in certain activities that require their input in relation to artworks in the galleries, visitors are notified that their reactions to or experiences of museum objects are valid. The immersive model proposed by Sitzia is parallel to the idea of participation in the museum space, in which visitors are immersed in the museum and immersed in the artworks, whereas the discursive model proposed by Sitzia relies on the traditional top-down model of the museum.

This also links with the Contextual Model of Learning, which posits that the physical, sociocultural, and personal contexts are fundamental to the learning process. Again, by asking participants to contribute, participatory practices draw upon visitors’ backgrounds, earlier experiences, dispositions, opinions, etc. and can also encourage visitors to participate with other visitors in a social manner, which is also a significant element of the learning process.

Through our three presentations, it became clear that learning is an experience in the museum space and encouraging active participation — to various degrees and in different manners — sets the learning process in motion.

The next steps forward

Although many museum researchers, academic, and practitioners would pat themselves on the back for researching participation within the museum space or implementing a participatory program at their institution, the academics and practitioners present at the MACCH conference in March 2017 stumbled upon something: participation is just an extension of that uni-directional model, isn’t it?

When we began to discuss what participation itself actually means, we realized that participation still implies that visitors or stakeholders are invited to partake in something. The fact that the institution has to grant the invitation means that the institution still holds the power; the museum grants an invitation on its own grounds and may still deny access depending on its own boundaries, wishes, desires, or needs.

Despite our attempts to focus more and more on our visitors, many museum practitioners — as well as visitors themselves, for that matter — often view aesthetic and social value as dichotomous, which Professor Gabriella Giannachi refuted outright in her keynote presentation about the epistemology of participation. In other words, increasing the social value or participatory practices within the museum space does not necessitate the diminishment of the aesthetic or artistic value of the museum objects, nor the intellectual value of curators and museums.

Hopefully, by inviting stakeholders and visitors to participate in the first place, this dynamic will begin to change; by inviting visitors on their own terms — not ours.

* * *

About the Author

DANIELLE CARTER is a freelance museum educator and researcher based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She studied Art, Art History, and Museum Studies (2013) at Florida State University before moving to the Netherlands to pursue her Master’s degree in Arts and Heritage: Policy, Management, and Education (2015) at Maastricht University. Through her experiences as an arts and museum educator in the United States and abroad, she has become interested in the museum (learning) experience, the narrative of the museum (learning) experience, interactions between visitors and museum objects, the mediatory role of the museum, and play in the museum space. In Amsterdam, she bikes, takes advantage of the sun every time it comes out, and falls in love with every dog that she sees. To find out more about Danielle’s activities, visit her website (tangibleeducation.nl) or send her an email at daniellencrtr@gmail.com.

DANIELLE CARTER is a freelance museum educator and researcher based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She studied Art, Art History, and Museum Studies (2013) at Florida State University before moving to the Netherlands to pursue her Master’s degree in Arts and Heritage: Policy, Management, and Education (2015) at Maastricht University. Through her experiences as an arts and museum educator in the United States and abroad, she has become interested in the museum (learning) experience, the narrative of the museum (learning) experience, interactions between visitors and museum objects, the mediatory role of the museum, and play in the museum space. In Amsterdam, she bikes, takes advantage of the sun every time it comes out, and falls in love with every dog that she sees. To find out more about Danielle’s activities, visit her website (tangibleeducation.nl) or send her an email at daniellencrtr@gmail.com.

Three academics dissect participation in science communication and museums for this special Spokes edition