Written by Mike Murawski

As common sense and straightforward as it sounds to think about museums as people- and human-centered institutions—a concept you’ve heard me write about quite a bit—this idea has faced a legacy of rather fierce opposition grounded in outdated traditions and histories. How many museums have mission statements that prioritize the colonizing actions of “collecting” and “preserving” objects, rather than fore-fronting the people-centered work of building community, growing empathy and understanding, celebrating human creativity, and cultivating engaged citizenship? How often do museum leaders and boards make decisions that value objects and collections over staff, volunteers, and museum visitors? What if museum leaders and professionals considered human relationships and human impact, first and foremost, when making decisions about exhibitions, interpretation, programs, facilities, policies, and practices? Embracing a human-centered mindset in museums asks us to do just that, advancing empathy, human potential, and collective well-being as integral elements to our institution’s values and culture. And this is not just putting visitors at the center of our thinking, but all of the people that make up a museum’s community—visitors, staff, volunteers, members, donors, and community partners as well as neighbors and residents of our localities and regions. All of these individuals are part of a museum’s interconnected human ecosystem.

Embracing a mindset of openness, participation, and social connectivity allows museums the chance to extend the boundaries of what is possible, and serve as sites for profound human connection in the 21st century. In their 2011 book Humanize: How People-Centric Organizations Succeed in a Social World, Jamie Notter and Maddie Grant discuss their ideas for developing a more human organization in a world affected by social media and the Internet.

“We need organizations that are more human. We need to re-create our organizations so that the power and energy of being human in our work life can be leveraged. This has the power not only to transform our individual experiences in the work world, but also to access untapped potential in our organizations” (p. 4).

Jasper Visser writes about museums and these aspects of a social business, quoting the Social Business Forum in defining a social business as “an organization that has put in place the strategies, technologies, and processes to systematically engage all the individuals in its ecosystem (employees, customers, partners, suppliers) to maximize the co-created value.” The model of a social business, therefore, focuses on building relationships and connections among its entire community, or ecosystem of people. For museums, this goes beyond just being visitor-centered and means thinking about staff and volunteers as well as neighbors and the broader public. As Visser states:

“museums and most other cultural institutions are inherently social organizations to begin with. They have always thrived on intimate relations with all individuals involved in the joint creation of value.”

Insert cliche image of people working together (couldn’t resist, sorry)…

This concept of a social museum relies on each and every stakeholder working together toward change, value, and impact (which is why using the stock image above actually makes sense to use in representing museums). The key elements of a social organization—embracing networks of people, considering social relationships inside and outside the organization, and enhancing collaboration in a way that crosses traditional boundaries—are all core to developing a human-centered mindset in museums.

Strategies for Change

So how can those of us working in museums begin to make this shift happen toward a more human-centered mindset? In order to become social organizations that achieve positive impact in their communities, museums need to be rethinking their internal organization structures. Most museums rely on deeply ingrained, top-down structures that rely on territorial thinking, defined protocols, and traditional reporting structures based on academic degrees, power, silos, division, and oppression. In these traditional hierarchies, communication flows from the top to the bottom which means that “innovation stagnates, engagement suffers, and collaboration is virtually non-existent” (Jacob Morgan, “The 5 Types of Organizational Structures: Part 1, The Hierarchy,” Forbes, July 6, 2015).

Furthermore, as stated in the nationwide report Ready to Lead: Next Generation of Leaders Speak Out (2008), organizations that maintain traditional hierarchies “risk perpetuating power structures that alienate emerging leadership talent in their organizations” (p. 25). The sluggish bureaucracy of this embedded management structure prevents a museum from being responsive to its staff and its broader community. In other words, traditional top-down museums are just not very human-centered. They tend to be leader-centered or focused on a few powerful individuals at the top. So how can this be changed? What steps can museum professionals take to think about and enact alternative structures?

To be more people-centered, museum leaders and staff can work toward more participatory, democratic, and flatter models for organizational structure. In their recent book Creating the Visitor-Centered Museum (2017), Peter Samis and Mimi Michaelson discuss this transformation taking place in museums taking a more visitor-centered approach: “new ways of working ultimately shift traditional structures and may end up equalizing roles or flattening hierarchies” (p. 6). Efforts to decentralize decision-making and promote broader collaboration lead to museums that are more innovative, more responsive to change, and more likely to have a shared central purpose across its staff, volunteers, visitors, and community stakeholders—its human ecosystem. When we rethink and replace the outdated hierarchies, there is clearly a greater potential for a broader base of individuals to feel personal ownership over the meaningful work of museums in their communities.

In 2011, the Oakland Museum of California (OCMA) made major changes to their structure that resulted in a new cross-disciplinary and cross-functional model focused on visitor experience and community engagement. Referred to within OCMA as “the flower,” this new organizational structure has attempted to rid the museum of some of the barriers formed by outdated ways of operating. In 2016, their updated organizational chart had “visitor experience & public participation” at its very center, and only text references to the CEO and executive team floating around the outside. What started as a “rake” of institutional silos, according to Executive Director Lori Fogarty, became a “flower” of cross-functional teams emphasizing transparency, input, and communication. The more decentralized flower structure has positioned this civic-minded institution to better serve and engage its community. Here is Fogarty speaking at an ArtsFwd event in 2014:

But What Can I Do?

Aside from reinventing your entire museum’s organizational structure (which is awesome, but quite challenging and rare), there are smaller action steps that anyone can take within their own institution.

One way to make these types of changes happen is to work toward flattening communication and expanding participation in decision-making. Seek ideas and input from staff and colleagues on a regular basis, and you don’t have to be a manager to do this. For example, instead of using meetings to passively report out information about upcoming projects or policies, use these times to also discuss critical issues and gather input. Even a large staff meeting can be a platform for two-way communication. In addition, empower staff at all levels to participate in setting goals for their departments and for the museum. This can happen at any level of an organization, and sometimes making changes at the smaller ‘grass roots’ level of an organization can eventually lead to significant changes at the top. And involving more staff input in goal setting may take a greater investment in time across an organization, it will lead to broader feelings of ownership once those goals are being implemented and achieved on the floor with visitors. Involving staff at all levels of an organization in goal-setting and decision-making can also work toward cultivating leadership at all levels. Human-centered museums are institutions that recognize leaders across all levels and departments, not just at the top.

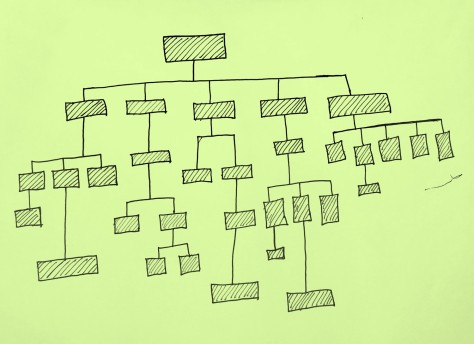

Finally, one important strategy for embracing a human-centered mindset in museums involves replacing outdated “org charts” with new ways of visualizing connections. Everyone reading this is probably familiar with the org charts that have each position in a box, and lines connect everyone based on management and reporting. Who manages who? Who evaluates who? Who has power over who? These charts fan out from the Director or CEO box at the top, ending at the bottom with lots of little boxes filled with part-time staff, security guards, volunteer docents, etc. Not only are these charts confusing (and oftentimes quite ugly), but they emphasize oppressive power relationships and do not accurately represent the way a museum works and how staff interact with each other.

Your museum or organization might have something that looks a bit like this:

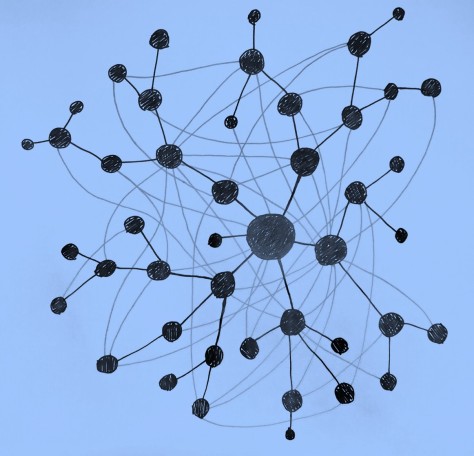

We need to replace these old org charts with new maps that emphasize human connection and collaboration. And you don’t need to be the human resources director or CEO to give this a try. Take a piece of paper, draw a circle to represent yourself, and then begin adding in other staff, volunteers, or partners based on your working relationships with them. Who do you collaborate with on a regular basis? What working group meetings or committee meetings do you attend? What are some of the social connections you have within your organization (yes, these count, too)? Soon, you begin creating an organic map of your organization based on human relationships and connection. Maybe something a bit more like this:

Not only is this a great way to visualize and map your existing connections with others, but you can also use this as a way to identify individuals or departments in your organization that you are currently not connected with. What are some ways you might begin to develop new connections to those people? What impact might building new connections have on your work, their work, and the museum’s work in the broader community?

Share Your Thoughts

These conversations and actions cannot take place solely behind museum walls or in the isolation of professional conferences. We need to work together to realize the full potential of museums and discover how a human-centered focus on social action can transform your practice, your museum, and your community.

Are you working toward rethinking hierarchies and outdated structures in your organization? Add your voice to the comments below or via social media (@murawski27), and share your experiences or questions as part of this effort to make change happen in museums.

Let’s be a part of making this change happen together!

* * *

Check out additional posts in this series about how museums might become more human-centered institutions working toward positive impact in our communities, including reflecting on personal agency as well as embracing a culture of empathy.

About the Author

MIKE MURAWSKI: Founding author and editor of ArtMuseumTeaching.com, museum educator, and currently the Director of Education & Public Programs for the Portland Art Museum. Mike earned his MA and PhD in Education from American University in Washington, DC, focusing his research on educational theory and interdisciplinary learning in the arts. Prior to his position at the Portland Art Museum, he served as Director of School Services at the Saint Louis Art Museum as well as coordinator of education and public programs at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University. Mike has been invited to lead workshops, lectures, panels, and training sessions at various institutions, including the Aspen Art Museum, Crocker Art Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, National Gallery of Art, Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Phoenix Art Museum, among others. He is passionate about how we can come to see museums as agents of change in their communities as well as creative sites for transformative learning and social action. Mike’s postings on this site are his own and don’t represent the Portland Art Museum’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

MIKE MURAWSKI: Founding author and editor of ArtMuseumTeaching.com, museum educator, and currently the Director of Education & Public Programs for the Portland Art Museum. Mike earned his MA and PhD in Education from American University in Washington, DC, focusing his research on educational theory and interdisciplinary learning in the arts. Prior to his position at the Portland Art Museum, he served as Director of School Services at the Saint Louis Art Museum as well as coordinator of education and public programs at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University. Mike has been invited to lead workshops, lectures, panels, and training sessions at various institutions, including the Aspen Art Museum, Crocker Art Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, National Gallery of Art, Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Phoenix Art Museum, among others. He is passionate about how we can come to see museums as agents of change in their communities as well as creative sites for transformative learning and social action. Mike’s postings on this site are his own and don’t represent the Portland Art Museum’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

Ahhhhhh…the org chart. The ungiving tree. How often I see it empower a few, and disempower the majority. I see how the title of “supervisor” or “manager” puts all the choice, the approval, the water and sunlight of a project, plan, idea, in their hands while so many are left to wait in the shade. It doesn’t fertilize creative work and it puts an immense level of expectation and stress on the few who nest near the top.

Like you, I think we can do better. The roots of a organization doesn’t come from the top leaves, but grows from the inside of a seed. We just need a few more good seeds. ❤️

Abby, thanks for your comment. I love your metaphors — yes, growth happens from the inside of a seed and from the roots.

This is a fantastic read! I’m about to state the obvious, but it must be said- most people can not afford to go to a museum and until that gets addressed in a major way, we will never get the diversity and inclusion we all seek. We must strategize about bringing the price down and I’m not talking about discounts to schools etc that I know museums work towards. Museums MUST ask themselves- HOW DO WE BRING THE ADMISSION COST DOWN? Otherwise we are just creating elitist organizations that talk the talk about inclusively but aren’t really doing anything real about it.

Thanks for your thoughts here, Tara. Yes, the admission cost is a hot topic now, given the Met’s recent decision. I think it’s always something to be considering. I know that many museums honestly rely on earned income and admission ticket sales to pay their staff and keep their doors open, so it’s a complicated equation. With that said, I think museums (and their donor bases) could be doing more work to build endowments specifically geared toward reducing and eventually eliminating admission costs. Donors love to fund special exhibitions and building projects, but don’t as often fund education, outreach, and access (with plenty of exceptions, of course). For many institutions, a moderate gift from a local Fortune 500 corporation could make this transformation possible. I’m probably oversimplyfing here (opening myself up to lots of follow-up comments, perhaps), but I do think this is an important part of the conversation around being a human-centered museum. Thanks for bringing it into this exchange.

Mike – Great post, you are singing my human-centered tune! Your thought-provoking article motivated me to put down some thoughts about how I conceptualize org structures, power and human relationships in the workplace. Hope you enjoy: https://thoughtsparked.blogspot.com/2018/01/organizational-structures-time-for-some.html

Thank you Mike. I read this a few days after a follow up conversation about the [many] issues raised by the Berkshire Museum deaccessioning. And it put that debate in a new light… our ethics policies prioritize (one might say fetishize) collections. The radical suggestion that we deaccession from the bottom of the collection (the 10% that will never be exhibited) to lower admission prices was widely criticized as naive or unethical (http://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/article/Art-museums-should-sell-works-in-storage-to-avoid-12489563.php) But that is just the sort of idea that puts people rather than objects at the center. As a field we need to talk about this more.

hi mike, this was a great post. i’m a first year museum studies student and was/am considering dropping out because i felt so depressed and angry that museums are so oppressive and constraining on an individual level. this post at least gave me some hope, so thank you very much :’)

Ellie, thanks for your kind words. I’m so glad that my perspective was uplifting for you. I completely understand your feelings of anger about museums — it’s been a rough year, and so many institutions are stuck in a set of outdated, oppressive practices and mindsets. That is certainly true. However, there are some really amazing institutions led by good people who are centering the human aspects of these institutions and thinking deeply about the role museums play within communities. I’ve been feeling a lot of anger these past 9 months, but I’m always trying to use that anger as a guide and a teacher to help me advocate for change and a better future. We can all commit to becoming changemakers and shape a new future for museums.