By Emily Wiskera, Laura Evans, Stephen Legari, Andrew Palamara

In an essay reflecting on how his past trauma influenced his experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, writer Geoffrey Mak said, “Our lives are not going back to normal, as one way of being has been abruptly and unilaterally aborted, without our consent. Instead, we’re left with the grief for tens of thousands of lives lost, trillions of dollars evaporated, and a future of promise that was wiped out for an entire generation.”

Mak speaks to something profound – a collective trauma – that many people are struggling to comprehend, the magnitude of which is still beyond our ability to envision or understand because it is ongoing. In our field, we’re grappling with acknowledging that loss alongside a desire to do what we can to ensure a better future. In light of this, four of us gathered over Zoom to talk about what we are calling trauma-aware art museum education. We wanted to figure out how we, as educators, can be more prepared to encounter trauma when the public returns to museums and how we can cultivate safe experiences for visitors to process the effects of these unprecedented times. We are sharing the transcript of the first convening of our trauma-aware art museum education (T-AAME) group.

Laura: Could everyone go around and introduce themselves and then we can jump into the topic of trauma-aware art museum education? Andrew, could you start us off?

Andrew: I’m Andrew Palamara, the Associate Director of Docent Learning at the Cincinnati Art Museum (CAM). I manage the training, evaluation, and recruitment of docents at the CAM.

Emily: I’m Emily Wiskera, Manager of Access Programs at the Dallas Museum of Art. I oversee educational programming for visitors with disabilities.

Stephen: I’m Stephen Legari, Program Officer for Art Therapy at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA). I facilitate museum-based art therapy groups, supervise interns, manage our community art studio, and collaborate on research.

Laura: And, I’m Laura Evans. I’m a professor at the University of North Texas and I run the Art Museum Education Certificate program. I am so happy we could all be together right now, thinking about this important topic. Maybe, before we jump in, we can talk about the terminology. “Trauma” is a pretty heavy term. How are we defining trauma in relation to COVID-19? Can we explain why we are using the words trauma-aware? What does that mean?

Stephen: Trauma is both a heavy term and a prevalent one. Our discussion around what it means to become trauma-aware as museum staff, particularly educators, is to both acknowledge with sincerity and respect that trauma is everywhere. But trauma is also highly subjectively experienced and expressed. Museums, by their nature, are environments where people’s collective and individual narratives are elicited and we cannot ignore, in good conscience, that this includes stories that are traumatic.

Laura: And, a result of this pandemic will inevitably include trauma: major traumas and micro-traumas. As you said, Stephen, we cannot, in good conscience, ignore these experiences of trauma when we return to our museums.

Emily: But, I think we should also keep in mind that not everyone will experience this pandemic as traumatic. For some, school and business closures may have removed them from otherwise toxic or trauma-inducing environments. Others may be experiencing multiple layers of trauma, as we are seeing with the tragic rise in domestic violence and child abuse cases. Experiencing trauma is an almost universal part of the human experience. But as in all situations, context and resources play a role. We should also be aware that in-depth processing of trauma likely won’t be immediate. We begin to work through trauma and start the process of healing when we feel emotionally safe to do so.

Laura: And, we can play a role in creating those safe spaces. But, before we talk about what that might look like, Andrew and Emily, do you want to tell us how and why you started thinking about trauma-aware art museum education and why you think it is important that we explore this right now?

Andrew: In January 2020, the Learning & Interpretation team at the CAM went through a half-day training on trauma-informed practice with Amy Sullivan, a local counselor with a private practice called Rooted Compassion. It revolved around understanding our own personal trauma before we begin to understand it in others. Once the pandemic hit the U.S., something clicked with me: this might be the most urgent time to formalize a trauma-aware approach to what we do at the museum. This is going to take a psychic toll on our personal lives and how we think about going to public spaces going forward. I reached out to Emily to see what she thought about it.

Emily: When Andrew reached out to me, I had been considering how the COVID-19 pandemic was affecting our communities and how the unique assets of the museum could be best used in response. Andrew’s thoughts about the public experiencing the pandemic as trauma connected with research that I had just stumbled upon. This early study out of China revealed a significant increase in acute Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms related to the pandemic. It seemed only natural to me that if the public was experiencing a change, that museums needed to adapt their strategies to be relevant and responsive to the experience of the public.

Laura: When Andrew and Emily came to me with this idea, I thought the perfect person to give some perspective was Stephen because of his training and his unique role as an arts therapist at the MMFA. Stephen, how does the MMFA already consider trauma in its programs and in its interactions with visitors?

Stephen: We have a community oriented practice in our education department that goes back more than 20 years. The model of project development was founded on co-creation with community and clinical partners. In this way, becoming informed about the needs of groups who may have been impacted by trauma grew organically. These could be folks living with mental-health problems, people with complex migration histories, people negatively impacted by their experiences as patients and the list goes on. Each collaboration taught us something new. Fast-forward to 2017 and we felt equipped to have a full-time program dedicated to actual therapeutic work.

Laura: Have any of us already had a trauma-aware experience at a museum or know of someone that has? Maybe one that you witnessed? If so, what was that like for you or for them?

Andrew: One of my colleagues, Sara Birkofer, led a discussion with a local art therapist of an exhibition by photographer Sohrab Hura called The Levee, and we explored the intersection of emotion and mental health through Sohrab’s photographs. We started with a quick mindfulness exercise, then talked about how the brain processes trauma. She guided us as we walked through the exhibition, which featured several dozen photographs of Sohrab’s travels through the American South as one artwork. That prompted us to think about how we gravitate toward images that reflect our mental state. It was really profound to hear how other people processed their life experiences through another person’s art, and I was floored by how quickly we established an environment of trust and openness with each other. Coincidentally, right before I attended the program, I had learned that one of my docents had passed away, and this conversation really helped me process that news in a meaningful way.

Emily: For me, a trauma-aware museum experience starts when the lived experience of the visitor takes priority over art history. Educators may drop in bits of historical information, but their primary goal is to encourage participants to build personally meaningful pathways to connect to art, and in turn, themselves. I witnessed this in action as an intern when my former colleague, Danielle Schulz, was guiding a discussion around a Roman sarcophagus. Danielle encouraged group conversation simply by having participants start by describing what they noticed. The conversation developed naturally, leading the group to discuss who would be entombed in a sarcophagus that depicted a battle scene. When Danielle asked, “What emotions does this object evoke for you?,” one participant shared that it reminded her of her daughter who passed away as an infant. The participant expressed that with the death of her daughter, she was mourning all of her daughter’s unrealized potential. She connected this feeling with the grown soldiers on the sarcophagus, wondering if the scene was a reflection of who the entombed person was, or what they might have been.

Laura: I have had communal experiences that are similar to what you two have just described but I’ve also had solitary experiences in art museums that have allowed me to process trauma. I was severely anorexic in high school and, after getting help, went through recovery for many years after. When I was doing my PhD, I focused on Lauren Greenfield’s exhibition, THIN, which is about women in treatment for their eating disorders. I first saw the exhibition at the Smith College Museum of Art and I walked through the show crying. Even though I wasn’t there with anyone, I saw lots of other girls and women crying, holding hands, patting one another on the back, and it made me feel connected to them in some way. I remember catching eyes with a guard and she gave me a sympathetic, understanding smile that made me feel like it was okay to continue processing in that space. I read through the visitor comment book and it was full of narratives of women who were similarly moved by the art. Even though I thought I had recovered by that point, that experience helped me heal in a way I didn’t know I needed.

Hearing about and talking through these stories was helpful to me in thinking about experiences we’ve already witnessed or participated in that we might consider to be trauma-aware. I know this is a seedling of an idea still, but what do we all think some of the characteristics are of what we are calling “trauma-aware art museum education” from the museum educator’s perspective? What could it look like? Sound like? Feel like?

Andrew: In my review of trauma-informed resources that I’ve come across, two key qualities have emerged: empowerment and connection. In museum education, these are givens. We’ve already embraced teaching practices that empower visitors to have a voice in their interpretation of art and their experience in a museum. With that, we put a great deal of emphasis on social connection, whether it’s active (a dialogue with visitors about art) or passive (watching a performance). But I think there’s a new urgency to these characteristics in a post COVID-19 world. More than ever, we need to make space in our programming to empower the public, as though they are not just recipients of our content, but active participants that find personal meaning in museums and the art inside of it. That goes hand in hand with our need to be socially connected to each other. I think we have tacitly acknowledged that by visiting museums and caring about culture; in other words, we go to museums because we want to feel connected to something bigger than ourselves. I think we saw this in the examples we just shared at the CAM, the DMA, and at Smith. Now, I think art museum educators have to make that social connection more direct and active, and we’ll have to be compassionate and creative in how we carry that out in practice.

Having said that, it’s not all about empowerment and connection. We have to consider qualities like building safety and trust with our visitors, resilience, patience, awareness of others in relation to ourselves, and reciprocity among many, many others. Emily, you’ve thought a lot about how the science behind trauma relates to what we do in museum education. Where have you seen connections between trauma and these ideas of empowerment and connection?

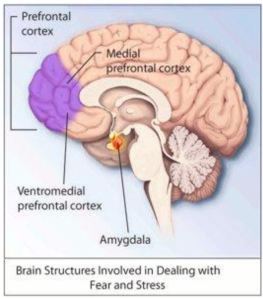

Emily: There are a few key attributes of trauma that inform the trauma-aware approach to museum education. First, is that trauma is not stored in the brain in the same way as other memories. Instead of being stored as narratives in our minds, traumatic events are imprinted on the amygdala through the emotional impact and sensory information experienced during the time of trauma- fragments of sound, smell, sights, taste or touch. A trauma-aware approach focuses on creating new emotional and sensory experiences that contradict the experience of trauma, replacing them with sensations rooted in safety, empowerment, and connection.

A second important note is that trauma is pre-verbal. Reliving traumatic events often shuts down the speech center of the brain, making it difficult to express the trauma in words. This information has great ramifications to our practice as museum educators. In our programs we have traditionally explored ideas through discussion. If we want to provide visitors with productive ways to express their experience, we need to open our practice to include more visceral, emotional, or sensory-based modes of engagement and response, rather than purely verbal ones. The good news is that a trauma-aware approach to museum education is in line with Universal Design principles of multi-modal engagement and is beneficial for all, not just those who have experienced trauma.

Stephen: It is to ask the question, how can art and art education/the art educator help facilitate experiences of containment, reassurance and safety? Trauma makes a better lens than a label. If we use trauma as a lens to appreciate both the intense difficulties some of our visitors faced and also the brilliance of the resilience to deal with those difficulties, then we can better adapt to them and encounter them with some kind of genuine presence. Seeing people as traumatized is simply pathologizing them and risks contributing to that trauma.

Laura: “A better lens than a label.” That is a good frame. What could trauma-aware art museum education look like from the visitor’s perspective? Sound like? Feel like?

Stephen: I am encouraged by what Ross Laird calls safe-enough museum experiences. If we accept that a great deal of museum content and exchange can be provocative for the visitor, then we have a framework of how to receive and manage those experiences. From the visitor’s perspective, I would encounter staff that are warm and genuine in their welcome. I would feel included even if it’s hard for me, as a visitor, to return that same measure of friendliness. I would be given some fair warning that museum content and activities can be challenging and that I might feel things. I might also be given some information about the limitation of the experience, i.e. that this is not therapy. And finally, I would encounter some flexibility in the pacing of the experience and in the attitudes of the staff who themselves can model calmness even if things get a little emotional.

Laura: Why do we think museums and art museum educators, in particular, are good places and people to do this kind of work?

Emily: The unique assets of the museum make it the perfect place for healing to begin. Since trauma affects the speech center of the brain, our public will likely be seeking out non-verbal modes to explore and express their lived experience. Visual art, a non-verbal mode of communication, is a natural fit. Another unique aspect of the museum is its ability to be a location for social interaction. Museums have moved beyond simply acting as stewards of objects or mausoleums of the past. Our value, as institutions and educators, lies in our ability to bring people together. Using art as a tool to make individual connections and share ideas, the museum provides an environment where we can be vulnerable and build social bonds. Socialization is our most fundamental survival strategy, but it is exactly this which breaks down in most forms of mental suffering and it is what we have lost during these months of pandemic isolation.

Laura: Yes, what makes museums so unique – our objects – also makes them ideal spaces for healing connections. We can all relate to objects; we all have a relationship with objects in our lives; we have all had a profound connection to an object. And, moving around, walking through, wheeling through a museum, coming close to look at a detail in a painting, moving around a sculpture; the physical movement that is required of touring a museum and looking at art can be helpful to process things too. Elliott, Lissa and Lilit do a beautiful job of emphasizing the importance of movement in museum education in their new book.

Andrew: I see this as an extension of the DEAI work that educators in the field have prioritized in recent years. Through scholars like Paulo Friere and bell hooks and resources like the MASS Action project and Museums Are Not Neutral movement started on this site, museum educators have acknowledged the injustices and inequalities that have plagued our society and our cultural institutions. Our work requires more empathy and action on our part to ensure that museums are truly for all of our communities. Today, we still see these inequalities as communities of color are disproportionately affected by the spread and treatment of COVID-19. Just like the Museums Respond to Ferguson movement in 2015, I think this is another moment in time when we can put our social obligations to the public in clearer view.

Laura: For all of us, it’s important to make a distinction between art museum education and art therapy. This trauma-aware approach can be therapeutic but isn’t intended to be therapy, right? In Museum Objects, Health and Healing, Cowan, Laird, and McKeown write about how museum staff can, “Facilitate the therapeutic — but don’t do therapy.” This is a really important distinction that I want to take some pains to highlight. Stephen, can you elucidate some of the differences between art museum education and art therapy in museums? Like, what do you want art museum educators to know about why and how their work is different than your work, for example?

Stephen: My colleague who runs our well-being program and I have had to really tease out what’s the difference between a program that’s well-being focused and a program that is therapeutic, that is a therapy program. As an arts therapist, what I want to help people with the problems that are present for them and use the museum and its resources as a tool to achieve some therapeutic goals. Sometimes that means being really present with the problem and staying with the participants as those layers are being revealed. In art therapy we are taking more risks and letting people know that discomfort and dealing with stuckness will be part of their journey. Whereas what my colleague aims to do is help people arrive and build positive experiences that are strengths-based, resilience-based, and pleasure-based. She and her collaborators meet people in the here and now and offer new experiences that help people leave feeling refreshed by their encounters with art and art-making. I can only imagine what a valuable resource that will be post-COVID; to feel refreshed by art and the people facilitating it.

Andrew: That brings up a question that I’ve had. Do you feel like there’s anything that museums have traditionally done in their educational programs that is not trauma-aware and we could dissuade each other from doing?

Stephen: I would say that any activity that prioritizes the information or the teaching, or even the outcome, over the participant experience is not trauma-aware. The sharing of participant’s material without their consent is not trauma-aware. And perhaps the presumption that our museums are for everybody is not trauma-aware. These are colonial institutions that have historically excluded an awful lot of voices and there is a need to be actively working on that history in the present in real-time.

Laura: I know you have The Art Hive at the MMFA. Can you tell us more about it and why an open studio like the Hive could be important in the wake of COVID-19? Why might this be a good thing for museum educators to implement post-pandemic?

Stephen: An Art Hive, or an open studio, I feel is a really positive, low-cost response to a diversity of needs. We know that giving visitors the opportunity to externalise their experience at the museum in some way is helpful and participatory. There are a range of responses that people have and need from art, some people need really structured experiences because it helps them feel re-contained and some people feel really encroached upon by the limitations of a structured experience. An open studio can accommodate both and really emphasize the autonomy of the visitor to make what they need to or seek the support they need to work through a creative response.

Laura: I love the idea of museums embracing the open studio concept in the wake of the pandemic, where people can use their hands to make what they feel moved to make and where they are tacitly or explicitly socializing with others in the museum. Like you said, Stephen, it is low cost and low risk but, potentially, high reward. Maybe now is a good time to wrap-up and pick this up again at another time?

Stephen: This is such a valuable conversation to be having across museums and across disciplines. I feel there is something tangible that will come of this in terms of our own education towards becoming trauma-aware and hopefully be of use to others.

Laura: I couldn’t agree more. It has been a true pleasure to connect during this time of disconnection and about such important work too. Let’s keep this conversation going. It feels like we are at the precipice of something that we should keep exploring. I hope there are others out there who are interested in thinking about this, talking about this, with us and that they will get in touch. Should we meet back in a few weeks to develop some more practical suggestions for how art museum educators can develop and facilitate trauma-aware programs?

* * *

About the Authors

LAURA EVANS is an Associate Professor of Art Education and Art History and the Coordinator of the Art Museum Education Certificate at the University of North Texas in Denton, Texas. Evans received her Ph.D. in Art Education, with a Museum Studies specialization, at The Ohio State University, a Master’s in Museum Studies at the University of Toronto, and a Bachelor’s in Art History and English at Denison University, Granville, Ohio. Evans has worked in museums from Australia to Washington DC to New Zealand. During non-COVID-19 summers, Evans lectures about art crime on cruise ships that sail the high seas. Laura’s email address is Laura.Evans@unt.edu

STEPHEN LEGARI is a registered art therapist and couple and family therapist. He holds a Master’s degree in art-therapy from Concordia University Concordia and another M.A. in couple and family therapy from McGill University McGill, where he won the award for clinical excellence. He has worked with a range of populations in numerous clinical, educational and community contexts. In May 2017, he became head of art therapy programs at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. He is currently the world’s only art therapist working full-time in a museum. Legari is a member of the MMFA’s Art and Health Committee. Stephen can be reached at slegari@mbamtl.org

ANDREW PALAMARA is the Associate Director for Docent Learning at the Cincinnati Art Museum (CAM). In this role, Andrew oversees the training, recruitment, and evaluation of the CAM docents. Prior to joining the CAM, he worked in education at the Dallas Museum of Art and MASS MoCA. He holds a BFA in Graphic Design and Illustration from Belmont University and a MA in Art Education from the University of North Texas. When he’s not at the museum, Andrew is most likely playing music or coaching his high school soccer team. Singing telegrams can be sent to Andrew at andrew.palamara@cincyart.org

EMILY WISKERA has worked in museum education since 2011, with a specialized focus on accessibility and working with diverse populations. As Manager of Access Programs at the Dallas Museum of Art, Wiskera oversees initiatives for visitors with disabilities, including programs related to dementia, Parkinson’s disease, autism, developmental or cognitive disabilities, and vision impairment.She is passionate about creating equitable experiences for all visitors. In her free time, Emily enjoys well-meaning mischief. Emily only receives carrier pigeons at EWiskera@dma.org

Featured Image: Family activities at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal. Photo by Caroline Hayeur

Interesting perspectives on complex concepts.

I think the idea of empathy forces museums to listen to other voices.

Very complex concepts. It’s amazing how the look pandemic has taken over so many areas of our everyday pleasures