Written by Andrew Palamara, Ronna Tulgan Ostheimer, Stephen Legari, Emily Wiskera, and Laura Evans

After our initial discussion of developing a trauma-aware practice, we have had several conversations about what T-AAME could become. We initially began thinking about T-AAME in reaction to the trauma inflicted by COVID-19, but it has taken on new urgency in recent weeks with the killing of George Floyd. We have spent time thinking about what would distinguish trauma-aware practice from our regular work as art museum educators. Wouldn’t best practice approaches already be sensitive and responsive to individual experience and need, including trauma? While the answer is yes, we believe T-AAME is still a little different.

Namely, unlike traditional art museum teaching and practice, T-AAME asks art museum educators to be mindful and responsive to implicit or explicit trauma. An awareness of trauma is no simple task, especially when most art museum educators are not trained therapists. The word ‘trauma’ itself encompasses many different human responses, but it still carries a heavy connotation in our society. It’s not safe to assume that all museum-goers will have experienced something traumatic prior to their visit, but everyone still deserves some compassion and care from us. Compassion and care are the core values of T-AAME from the art museum educator’s perspective, while connection and empowerment are two of the main goals for visitors.

According to recent surveys conducted by Wilkening Consulting, museum-goers have strong reservations about participating in guided tours or programs in the galleries when they visit museums again. We will have to confront a new set of limitations and reinvent our best practices in response. As we continue to develop and refine T-AAME, we have developed a list of supportive and foundational resources about trauma that have informed our approach (see the end of this post for an access link). We hope to continually update this list and welcome others to contribute resources as well. We have also begun to articulate some principles and practices of T-AAME. We believe these ideas can be applied to online and in-person programs and are practices that could easily and safely be incorporated into our work as we return to museums. Many are approaches with which you are, no doubt, already familiar and we are highlighting them here to emphasize that certain practices are already sensitive to trauma. Others may be new approaches or only require slight modifications to make widely-used practices more trauma-aware.

PRACTICE

Creating Relationships with Trained Therapists

We know that good art museum education, especially practices that focus on personal interpretation and perspective, can be therapeutic without being therapy. But, because T-AAME is at the intersection of art museum education and therapy, we strongly advocate for working with a licensed therapist who has training in trauma-informed practice and experience working with groups and/or teaching. Many therapists regardless of their modality can help with this initiative. Art therapists, we feel, might be especially well placed to work with given their strong connection to the creative arts and to dialoguing with and through art objects. You can find a list of registered art therapists in your area through the Art Therapy Credentials Board or the American Art Therapy Association.

Preparing a Tour & Preparing your Group

To borrow from art therapy language, setting the frame is an important activity at the outset of a group visit. Set the boundary around what participants can expect from an experience and also the limitations of what the experience can provide. It is important to adapt language and attitude for different groups and their needs. It is also worth noting that this does not mean we are always engaging in serious talk and dire warnings. Helping to get yourself and your group ready should come from a place of warmth, openness, curiosity and can include playfulness and humour. Understanding the goals of the visit can inform our style of preparation. This holds true for virtual visits and live ones.

When planning a tour or program, carefully consider the individual identities within your group to select appropriate works of art and topics of discussion. Along with being aware of the group, it is also important to be aware of your own presence. Do you have any particular stressors that you need to be aware of? Develop and practice techniques to center yourself and manage your own emotional activation when facilitating a group.

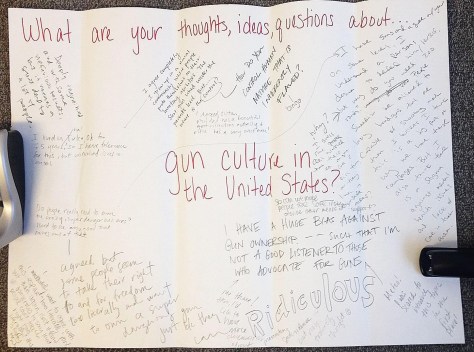

Brian Arao and Kristi Clemens (2013) write about establishing brave spaces instead of safe spaces for dialogue. They advocate for groups to create ground rules for discussion together so that terms like “safe” and “judgment” are defined clearly by everyone involved. For example, when starting a conversation about a social justice issue in the museum, you might begin by asking, “What do you all need from each other to be honest and vulnerable in this conversation?” This makes time for the group to collectively set the terms for their interaction with each other.

While Arao and Clemens use this as a framework for conversations about social justice, it could be adapted as a more compassionate opening to any museum program. In the coming months, museum visitors will likely feel some kind of anxiety about sharing an enclosed public space with other people. If you are facilitating some kind of program in the galleries, you might ask your group, “What do you feel comfortable doing together?”

As explained in Museum Objects, Health and Healing, it is important to craft appropriate warnings for potential emotional activation when looking at and talking about art. Avoid using terms like “trigger warning” or cautioning the group in a way that will increase anxiety. Instead, select terms that encourage visitors to apply their own emotional skills to navigate and stay in control of their experience. Cowan, Laird, and McKeown (2020) offer a few suggestions:

“Remember to take care of yourself. You decide how much of this to see. Some visitors have strong reactions. Your reactions are unique to you. It’s okay to be emotional. Reach out if you need help. Do this in your own way” (p. 183).

Group Discussion and Dynamic

Facilitating careful and sensitive conversations is a critical part of art museum education, and paraphrasing or re-voicing (O’Connor & Michaels, 1996) is widely considered to be a best practice in these discussions. In T-AAME, we advocate for a scaffolded approach to paraphrasing, which eventually results in participants speaking to one another, rather than to or through the facilitator or mediator.

Terry Barrett visited with a group of Laura’s university students in the fall of 2019, before COVID-19, and facilitated many discussions about works of art. Barrett set up several ground rules before the conversations started. He asked us to speak loudly and to one another (and not to him) so that everyone could hear. He would frequently remind the group to talk to each other. He melded into the group – sometimes standing with us, sometimes behind us, sometimes in front of us – giving us the feeling that he was with us rather than removed from us. Barrett asked for no side conversations (anything that wanted to be shared to a neighbor, could be shared with the group) and no put-downs, and emphasized that listening was as important as talking. If he couldn’t hear someone, he would simply ask for them to speak up or ask the person farthest from the speaker if they could hear. Very occasionally, he would paraphrase, if what was shared was a complicated idea or if he needed clarification. Mostly, he asked provocative questions and moved the conversation forward as the group spoke to one another. He listened far more than he spoke and he emphasized to the group that listening was a form of participation.

Inspired by Barrett, we believe that limited paraphrasing can be a T-AAME practice as it empowers the participant to speak without mediation and connects members of a group. We think this works best with older participants (not “littles”) and can be eased into or scaffolded by starting out with more traditional paraphrasing and slowly stepping back while introducing the rules of speaking loudly and to one another, while avoiding side conversations and put downs. The ultimate goal is for participants to be speaking directly to one another, responding to one another, and feeling connected to one another.

Modes of Response and Engagement

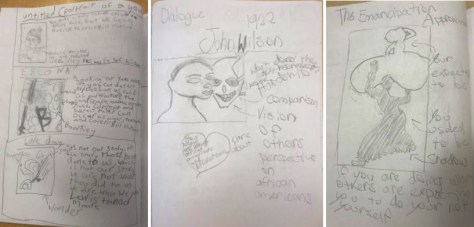

Allow for the time and space for deep reflection to occur. Instead of always asking visitors to verbally respond to a work of art as part of a conversation, pass out paper/notecards and pencils for written responses.[1] Tell your participants, up front, that the writing is completely anonymous, that you don’t want them to write their names on their responses, and that after everyone is finished writing, you will randomly read some of the notecards out loud. Ask a question or provide a clear, open prompt that gives participants the opportunity to express themselves, emotionally or creatively. They can write just a few words, a poem, a story, or whatever comes to mind as it relates to the question or prompt. After giving the group time to respond, collect the responses. Shuffle the cards and read them out loud without providing any commentary. The responses are for the group to hold in their mind, but not to critique or comment on. An added benefit of this activity is that it can be comfortably done while wearing a mask.

Another trauma-aware approach focuses on creating new sensory experiences that contradict those of trauma, replacing them with sensations rooted in safety, empowerment, and connection. One method is to incorporate multi-sensory objects or prompts into your program, as is commonly done as a best practice. For example, if discussing the process of mummification in Ancient Egypt while exploring an object like the Dallas Museum of Art’s Coffin of Horankh, participants could feel a piece of linen wrap or smell frankincense and myrrh, two oils used in the embalming process. If shared touch objects are of concern in the short-term, ask visitors to touch something of their own, such as their purse or clothing and make a sensory connection to an object they find in the galleries. Use their selection as a point of discussion.

Sensory exploration can also be done verbally. If exploring a scene such as Mountain Landscape with an Approaching Storm, the group could be prompted to describe a place that they have been to that looks or feels similar to the scene in the painting. If they were inside the scene of the painting, what would they hear? Feel? Smell? Taste? If they were amongst the group of villagers in this painting, what path would they take to castle on the hill? What would they encounter along the way?

In Activity-Based Teaching in the Art Museum (2020), Kai-Kee, Latina and Sadoyan illustrate an approach to eliciting low-risk, movement-focused emotional responses from a group:

Our group collects in front of Portrait of Madame Brunet (ca. 1861-63), an early work by Édouard Manet. “If you like this,” Lissa begins, “stand to your right. If you don’t, stand to your left.” Her word choice is intentionally open ended. “This” could mean the person depicted in the portrait, the way in which she is represented, the painting style, the artist, and so on, or a combination of factors. “Take a moment to really think about this question, and tap into your reaction.” Lissa is purposefully slow in leading the group through these steps, creating space for her visitors to sensitize themselves to the work for their emotions to unfold over time. As the participants start to move their bodies in response to the prompt, Lissa adds another dimension: “Stand closer to the painting if it is a strong feeling, and farther back if it is the opposite. If you are undecided, you might find yourself in the middle.” She then invites the group to share the reasons why they have selected their current positions. “Please listen to others’ responses,” she adds. “They might even affect your decision. Feel free to change your mind, and your position, if you find someone else’s reasoning compelling.”(pg. 134)

We consider Kai-Kee, Latina, and Sadoyan’s approach to be trauma-aware for several reasons. It allows participants to incorporate movement as a mode of response and it acknowledges different levels of trust within a group. Participants are able to share as much or as little as they feel comfortable and to demonstrate reciprocity by changing their position in response to others’ ideas. This approach empowers the visitor by valuing their feelings and opinions while also connecting visitors by giving them the opportunity to observe and react to others.

Making

Until recently, participatory opportunities for museum visitors were an important way for them to be able to externalize something of their lived experience and enter into creative dialogue with the larger museum community. Open studios, creative workshops, arts-based and written feedback, and community exhibitions are all well-established tools that art educators have used to connect with their participants and connect their participants to the museum. COVID-19 has presented serious constraints about the safe use of art materials.

As creative professionals, the education teams in museums have been quickly adapting and are using a number of simple, digitally-based tools. These include participants sharing their artwork made at home, photography, and digital-art. The gradual return to live encounters means that participants will not be sharing materials for some time. Organizing with groups to bring and use their own materials is one solution. Another is the exclusive use of easily disinfected materials such as markers, scissors, colored pencils, paintbrushes, needles, and knitting / crochet tools. But, the intention and use of participatory activities remains important and perhaps even more so as we consider the traumatic impact of COVID-19 on large portions of our populations.

The American Art Therapy Association has a guide for best practice of the use of art materials based on CDC recommendations.

The studio remains an important practice whether live at the museum using the appropriate guidelines or in the virtual studio. Along with empowerment through art-making, the art studio will continue to be a place for social connection. The careful attention of facilitators, the casual conversations, and the sharing of work are all essential ingredients in maintaining the connections to communities and visitors that educators have built over many years.

Google Doc for Resources:

Inspired by La Tanya S. Autry’s Social Justice & Museums Resource List, we started an open-source document of trauma-focused resources:

TRAUMA-AWARE ART MUSEUM EDUCATION RESOURCE LIST

We hope that you will contribute to this document and share it with colleagues. Likewise, we welcome any and all feedback on T-AAME. We are grateful and buoyed by the responses we have received so far and we would appreciate hearing about your experiences incorporating any of these practices into your work.

* * *

Works Cited

Arao, B., & Clemens, K. (2013). From Safe Spaces to Brave Places: A New Way to Frame Dialogue Around Diversity and Social Justice. In Landreman, L. (Ed.), The Art of Effective Facilitation (pp. 135-150). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Cowan, B., Laird, R., & McKeown, J. (2020). Museum Objects, Health and Healing: The Relationship Between Exhibitions and Wellness. Milton Park, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Kai-Kee, E., Latina, L., & Sadoyan, L. (2020). Activity-based teaching in the art museum: Movement, Embodiment, Emotion. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

O’Connor, M., & Michaels, S. (1996). Shifting participant frameworks: Orchestrating thinking practices in group discussions. In D. Hicks (Ed.), Discourse, learning, and schooling (pp. 63-103). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

[1] This is another engagement strategy that Laura has witnessed and participated in when teaching with Terry Barrett.

* * *

About the Authors

LAURA EVANS is an Associate Professor of Art Education and Art History and the Coordinator of the Art Museum Education Certificate at the University of North Texas in Denton, Texas. Evans received her Ph.D. in Art Education, with a Museum Studies specialization, at The Ohio State University, a Master’s in Museum Studies at the University of Toronto, and a Bachelor’s in Art History and English at Denison University, Granville, Ohio. Evans has worked in museums from Australia to Washington DC to New Zealand. During non-COVID-19 summers, Evans lectures about art crime on cruise ships that sail the high seas. Laura’s email address is Laura.Evans@unt.edu

STEPHEN LEGARI is a registered art therapist and couple and family therapist. He holds a Master’s degree in art-therapy from Concordia University Concordia and another M.A. in couple and family therapy from McGill University McGill, where he won the award for clinical excellence. He has worked with a range of populations in numerous clinical, educational and community contexts. In May 2017, he became head of art therapy programs at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. He is currently the world’s only art therapist working full-time in a museum. Legari is a member of the MMFA’s Art and Health Committee. Stephen can be reached at slegari@mbamtl.org

ANDREW PALAMARA is the Associate Director for Docent Learning at the Cincinnati Art Museum (CAM). In this role, Andrew oversees the training, recruitment, and evaluation of the CAM docents. Prior to joining the CAM, he worked in education at the Dallas Museum of Art and MASS MoCA. He holds a BFA in Graphic Design and Illustration from Belmont University and a MA in Art Education from the University of North Texas. When he’s not at the museum, Andrew is most likely playing music or coaching his high school soccer team. Singing telegrams can be sent to Andrew at andrew.palamara@cincyart.org

RONNA TULGAN OSTHEIMER has worked in the education department of the Clark for more than eighteen years, first as the coordinator of community and family programs and then, for the past nine years, as director of education. Her goal as a museum educator is to help people understand more fully that looking at and thinking about art can expand their sense of human possibility. Before coming to the Clark, Tulgan Ostheimer taught at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in the education department. She holds an EdD in psychological education from the University of Massachusetts and a BA in Sociology and American Studies from Hobart and William Smith Colleges. She can be reached at rtulgan@clarkart.edu

EMILY WISKERA has worked in museum education since 2011, with a specialized focus on accessibility and working with diverse populations. As Manager of Access Programs at the Dallas Museum of Art, Wiskera oversees initiatives for visitors with disabilities, including programs related to dementia, Parkinson’s disease, autism, developmental or cognitive disabilities, and vision impairment.She is passionate about creating equitable experiences for all visitors. In her free time, Emily enjoys well-meaning mischief. Emily only receives carrier pigeons at EWiskera@dma.org

* * *

Featured Image: A mediator (educator) at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts working with children. Photo credit © Mikaël Theimer (MKL)

ALLI ROGERS ANDREEN: Community Engagement Coordinator at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. She develops and collaborates on a variety of programs, and works primarily with multi-generational groups, teens, and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. She thoroughly enjoys collecting resources, capturing strange smells, making sound suits, and crowing like a rooster in the galleries. She received her MA in Museum Education with a Certificate in Art Museum Education from the University of North Texas and her B.F.A. in Studio Art from Texas State University.

ALLI ROGERS ANDREEN: Community Engagement Coordinator at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. She develops and collaborates on a variety of programs, and works primarily with multi-generational groups, teens, and adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. She thoroughly enjoys collecting resources, capturing strange smells, making sound suits, and crowing like a rooster in the galleries. She received her MA in Museum Education with a Certificate in Art Museum Education from the University of North Texas and her B.F.A. in Studio Art from Texas State University.

HOLLY GILLETTE is an art museum educator with an interest in gallery teaching and community building. She is currently an Education Coordinator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) where she oversees the school and community partnership program Art Programs with the Community: LACMA On-Site. Prior to working at LACMA, she began her career in Museum Education at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, CA, focusing on school, early childhood, and family audiences. Holly holds a MS.Ed. in leadership in museum education from the Bank Street College Graduate School of Education and a B.A. in art history and studio art from University of California, Davis. Holly’s postings are her own and don’t necessarily represent LACMA’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

HOLLY GILLETTE is an art museum educator with an interest in gallery teaching and community building. She is currently an Education Coordinator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) where she oversees the school and community partnership program Art Programs with the Community: LACMA On-Site. Prior to working at LACMA, she began her career in Museum Education at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, CA, focusing on school, early childhood, and family audiences. Holly holds a MS.Ed. in leadership in museum education from the Bank Street College Graduate School of Education and a B.A. in art history and studio art from University of California, Davis. Holly’s postings are her own and don’t necessarily represent LACMA’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

Because the children expect to find a place for themselves in the things we do in school, I knew I could expect authentic attempts at making meaning of the art in the “Constructing Identity” exhibition, and so I needed to focus on setting them up to be able to share the meanings they were making. My goal was to support the children to see each piece in the collection as a kind of long-distance offer of connection from one artist to another. I didn’t need to tell them how to connect with the art, how to find meaning in it — I just needed to ask them to, and I needed to give them some tools to do so.

Because the children expect to find a place for themselves in the things we do in school, I knew I could expect authentic attempts at making meaning of the art in the “Constructing Identity” exhibition, and so I needed to focus on setting them up to be able to share the meanings they were making. My goal was to support the children to see each piece in the collection as a kind of long-distance offer of connection from one artist to another. I didn’t need to tell them how to connect with the art, how to find meaning in it — I just needed to ask them to, and I needed to give them some tools to do so.

SUSAN HARRIS MACKAY is Director of Teaching and Learning at Portland Children’s Museum. In that role, she gives leadership to Opal School and the Museum Center for Learning, and works directly with children in the classroom. Opal School serves children ages 3-11 using inquiry-based approaches through the arts and sciences with a mission to strengthen education by provoking fresh ideas concerning environments where creativity, curiosity and the wonder of learning thrive. Along with her colleagues, Susan shares these fresh ideas through a professional development program for educators world-wide. Recent work includes chapters in Fostering Empathy Through Museums, and In the Spirit of the Studio, 2nd Edition, and a TEDx talk called, “School is For Learning to Live”. Connect with Susan and Opal School at opalschool.org.

SUSAN HARRIS MACKAY is Director of Teaching and Learning at Portland Children’s Museum. In that role, she gives leadership to Opal School and the Museum Center for Learning, and works directly with children in the classroom. Opal School serves children ages 3-11 using inquiry-based approaches through the arts and sciences with a mission to strengthen education by provoking fresh ideas concerning environments where creativity, curiosity and the wonder of learning thrive. Along with her colleagues, Susan shares these fresh ideas through a professional development program for educators world-wide. Recent work includes chapters in Fostering Empathy Through Museums, and In the Spirit of the Studio, 2nd Edition, and a TEDx talk called, “School is For Learning to Live”. Connect with Susan and Opal School at opalschool.org.

As I thought about this dichotomy, I remembered Rebecca Solnit’s writings and her ability to capture seemingly contradicting ideas, such as finding oneself in the process of getting lost. Serendipitously, this year, she wrote a new foreword to her 2004 book

As I thought about this dichotomy, I remembered Rebecca Solnit’s writings and her ability to capture seemingly contradicting ideas, such as finding oneself in the process of getting lost. Serendipitously, this year, she wrote a new foreword to her 2004 book  In 1970, anthropologist Margaret Mead sat with writer and social critic James Baldwin in a

In 1970, anthropologist Margaret Mead sat with writer and social critic James Baldwin in a  MICHELLE DEZEMBER is the Learning Director at the Aspen Art Museum, where she oversees all aspects of education, public programs, and interpretive projects. Previously, she was Deputy Director of Programming and Special Projects at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Qatar, where she also served as Acting Director and Head of Education. She has also worked as a museum educator in California and New York, and as a Fulbright scholar at the Museum of the History of Immigration in Barcelona. She holds a dual degree in Art History and Sociology from Santa Clara University, a diploma in Visual Cultural Studies from the University of Barcelona, and an MA in Museum Studies from the University of Leicester.

MICHELLE DEZEMBER is the Learning Director at the Aspen Art Museum, where she oversees all aspects of education, public programs, and interpretive projects. Previously, she was Deputy Director of Programming and Special Projects at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Qatar, where she also served as Acting Director and Head of Education. She has also worked as a museum educator in California and New York, and as a Fulbright scholar at the Museum of the History of Immigration in Barcelona. She holds a dual degree in Art History and Sociology from Santa Clara University, a diploma in Visual Cultural Studies from the University of Barcelona, and an MA in Museum Studies from the University of Leicester.