Editor’s Note: While ArtMuseumTeaching.com does not frequently republish posts from other sites, there are interesting and urgent issues raised periodically that, I feel, could spark productive conversations, exchange, and potentially even change in our field. The provocative post below published at Opine Season has already sparked lots of thinking and questioning, and I’d like to utilize the online space and community of ArtMuseumTeaching.com to allow for an OpenThink on these meaningful issues of diversity, audience, community, and social responsibility. As the letter’s authors state below, “we write this not as disgruntled individuals wanting access to one event. We write this as a collective who are asserting their voice to hold the institutions in their community accountable to a higher responsibility of service.” I invite everyone to share thoughts, questions, and experiences below.

Written by Chaun Webster, Jeremiah Bey Ellison, Arianna Genis, Shannon Gibney and Valerie Deus

Originally posted at Opine Season on October 29, 2013.

To Whom It May Concern at The Walker Art Center,

We have learned that on October 30, The Walker Art Center will be showing the film, 12 Years a Slave, directed by Steve McQueen, and followed by a talk with the director on Nov 9. This film is perhaps one of the most honest and visceral visual representations of the horrors that were part and parcel of the institution of slavery. Furthermore from the beginning, 12 Years a Slave has been, from its firsthand account, to the writer, to the director and leading actor, one of the most highly recognized, fully Black cinematic collaborations in the history of film.

We are concerned that though this film is being shown, that peoples of African descent, whose ancestors’ lives and histories were disrupted by the slaveocracy, will be largely underrepresented in the audience. Our position is that equity is not just about the diversity in the art being shown but the material work of creating greater access to exhibitions to ensure that audiences are representative of the subject matter.

We are concerned that though this film is being shown, that peoples of African descent, whose ancestors’ lives and histories were disrupted by the slaveocracy, will be largely underrepresented in the audience. Our position is that equity is not just about the diversity in the art being shown but the material work of creating greater access to exhibitions to ensure that audiences are representative of the subject matter.

We understand that these events were publicized to members of The Walker and on The Walker’s website. As you may or may not know, when marketing strategies are limited in media and points of origin, the race, class, gender and other layers of social location are also limited.

Within the Walker Art Center’s Mission Statement the institution is described as “a catalyst for the creative expression of artists and the active engagement of audiences” and having programs which “examine the questions that shape and inspire us as individuals, cultures and communities.” Which communities do you seek to inspire and what questions do you seek to examine with the creative expression of artists?

Over the years we have become acutely aware of the way that art institutions are guided by an exceptionalism that will welcome works of art by select artists of African descent and other historically marginalized groups but will largely have little to no relationship with members of those communities. This in no small way contributes to the issue of representative audiences.

Representative audiences insure that narratives are not placed in a vacuum where art institutions can be absolved of responsibility to the cultures and traditions that those stories come from. When white-dominated spaces, often of a homogenous class, bring work like McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave in, they in many ways manage the narrative and the way that it gets interpreted. In these spaces the participant/viewers are freed of any responsibility, social or otherwise, to historically marginalized groups and in so doing re-inscribe the roles of colonialism in art production, distribution, and consumption. In other words, in this case, African art can be present and maybe even a few “exceptional” African artists, but by and large African bodies are unwelcome.

Representative audiences insure that narratives are not placed in a vacuum where art institutions can be absolved of responsibility to the cultures and traditions that those stories come from. When white-dominated spaces, often of a homogenous class, bring work like McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave in, they in many ways manage the narrative and the way that it gets interpreted. In these spaces the participant/viewers are freed of any responsibility, social or otherwise, to historically marginalized groups and in so doing re-inscribe the roles of colonialism in art production, distribution, and consumption. In other words, in this case, African art can be present and maybe even a few “exceptional” African artists, but by and large African bodies are unwelcome.

In light of all of this we are calling on The Walker Arts Center to recognize their exclusive practice of not intentionally involving historically marginalized groups at the table for this occasion. This recognition can in part take the form of publishing this letter as an addendum to the material circulated at the screening of 12 Years a Slave and director talk.

We urge The Walker to open up more ticket space for both the screening and the discussion with Steve McQueen. This ticket space would be freely given to reputable organizations of our choice that work with underrepresented youth.

We urge The Walker to arrange another screening and talk with the director that we would host in a community space of our choosing.

Lastly we are calling on The Walker to host a panel discussion at The Walker where we can convene a public conversation on art and social responsibility as it relates to the artist and art institutions.

The tremendous contributions of Africans, on the continent, in the United States, and other parts of the diaspora cannot be understated. These contributions stand in chorus with that of other historically marginalized groups whose communities continue to be denied access to tables carved from their own wood.

The Walker can serve a role in equity as it relates to the production, distribution, and consumption of art in the Twin Cities, but that will require a resolve to listen to its diverse constituents who represent a variety of cultural and ideological perspectives. We write this not as disgruntled individuals wanting access to one event. We write this as a collective who are asserting their voice to hold the institutions in their community accountable to a higher responsibility of service. It is our belief that this is not only possible but imperative as we move forward.

* * * * *

About the Author

Chaun Webster is a Twin Cities activist, publisher, and poet in the Black radical tradition. Founding Free Poet’s Press in 2009 with the intention of empowering Black and Brown artists to control their own images, Webster is a 2011 Verve Grant recipient and is preparing for the release of HaiCOUP: a fieldguide in guerrilla (po)ethics. More information about Chaun Webster and Free Poet’s Press can be found at www.freepoetspress.com.

Chaun Webster is a Twin Cities activist, publisher, and poet in the Black radical tradition. Founding Free Poet’s Press in 2009 with the intention of empowering Black and Brown artists to control their own images, Webster is a 2011 Verve Grant recipient and is preparing for the release of HaiCOUP: a fieldguide in guerrilla (po)ethics. More information about Chaun Webster and Free Poet’s Press can be found at www.freepoetspress.com.

RELATED POSTS THAT MIGHT BE OF INTEREST:

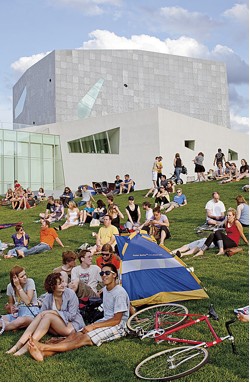

Blurring the Lines: Walker Art Center’s Open Field

Reflecting on Our Radical Roots

Making the Conversation More Inclusive