Written by Chelsea Emelie Kelly, Park Avenue Armory

This article is a case study about the impact of “unplugging” as it relates to reflective practice for youth and educators. If you’re interested in exploring reflection more broadly, and you’ll be attending the 2016 National Art Education Association Conference in Chicago next week, please join Mike Murawski and myself for our session “Reflective Practice in Museum Education” on Thursday, March 17 at 12 noon (McCormick Place/Lakeside Center/E271a). We’ll unpack reflective practice for museum educators in an interactive, conversational session—we hope to see you there! If you can’t join us, please comment here, tweet us (@chelseaemelie and @murawski27), or follow #NAEAReflect.

When talking about unplugging, we always think of technology. However, I define unplugging as a way of regaining full control of yourself, physically and mentally, in any circumstances.

—Isatu, high school senior, Phase II Youth Corps

In the summer of 2015, a group of New York City high schoolers and college freshmen, students in the Park Avenue Armory Youth Corps program, gather in the Board of Officers room at the Armory, reclined on lean-back floor seating in front of a grand piano. There is a buzz of anticipation in the air, which turns to quiet excitement when two world-class artists enter the room: performance artist Marina Abramović and pianist Igor Levit.

During the next hour, Abramović and Levit give the students a crash course in unplugging and being present, major themes of their upcoming winter production—a hybrid performance/immersive experience to introduce audiences to a new method of engaging with classical music. Over the next few months, inspired by Abramović and Levit, a number of these students will deeply explore the concept of unplugging: what it is, why do it, and the unexpected realizations it can evoke about our own selves.

Although some might stereotype today’s teenagers as one of the most “plugged-in,” smartphone-obsessed generations of all time, our students offered sophisticated, thoughtful reflections about how we can truly connect with each other and better understand ourselves. As one of the educators facilitating this project, I had the unique opportunity to experience this deep dive into unplugging alongside my students. This post explores both the impact of “unplugging” and reflective practice on teens as well as its impact on me as a teacher, and offers ideas about how we might apply the benefits of unplugging to our practice as art educators and museum leaders.

The Project: Goldberg and the Guide to Unplugging

We understand that not many people today know what it is like to be left in silence, stripped from their cellular devices, or even just stare into someone’s eyes… We stepped out of our comfort zone and… left wanting to try it again.

—Terrelle, high school senior, Phase II Youth Corps

Igor Levit and Marina Abramović’s Goldberg (which ran December 7–19, 2015 at Park Avenue Armory) required patrons to lock up their cell phones, watches, and personal belongings in lockers, then sit in silence in the Armory’s Drill Hall for 30 minutes to “unplug” and mentally prepare themselves to be present to listen to Johann Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations, performed by Levit. Abramović’s method for listening to music was experienced by thousands, including New York City public high school students in a student matinee.

The Youth Corps students were charged with developing ways to help their peers prepare for this uncommon experience. First, Youth Corps researched the artists and concepts behind Goldberg, familiarizing themselves with Bach, Levit, Abramović, performance art, and “slow” movements, from slow art to slow TV. They met with former Armory artist-in-residence Helga Davis, a vocalist and performance artist, who led the students through an activity in which they stared into each other’s eyes, opening themselves to their peers in a new way. They visited current artist-in-residence Imani Uzuri, whose singing and installation inspired by Sister Gertrude Morgan helped Youth Corps center themselves in mind and body.

A printed Guide to Unplugging became one of two facets of the project. As their driving question for the guide, the Youth Corps responded in writing to the question: What is worth unplugging for? They used verbal storytelling and peer editing to brainstorm and solidify their ideas. Their written responses ranged from getting in tune with nature to bike-riding with no destination in mind, from challenging oneself to communicate with family members, to getting lost in artmaking. Others talked of experiencing theater or acting, and some about meditating or being present on their morning commutes. Across the board, students acknowledged the importance in getting out of your comfort zone in order to unplug—and how worth it the challenge of being present is.

You can read the full Guide to Unplugging here.

For the student matinee, and the second part of their final project, the Youth Corps assisted none other than Marina Abramović herself in creating a short pre-show for 450 students. Although the students had already been introduced to the production through a pre-visit from Armory Teaching Artists, this pre-show experience would ensure that students were present and ready for Goldberg itself. Over two meetings, Youth Corps spoke with Abramović about her method and process, and how Levit and the Goldberg Variations dovetailed with her own art practice. When the Youth Corps asked for any tips she had for experiencing Goldberg, Abramović led the group in an immersive breathing exercise—and it was so powerful that it quickly became clear that the pre-show should include the same. As Lizmarie described:

[Abramović had us start] by lying on the floor with our faces to the ceiling and having our hands to our hearts and stomachs. I felt like I was floating in the middle of the ocean, and found the comparison between the motion of the waves and the beating of my heart. That is when I realized I was in a full state of relaxation. To me, the noises of kids in the hallway outside faded into a nice summer day with seagulls and waves crashing onto the shore.

—Lizmarie, high school junior, Phase I Youth Corps

And so the Youth Corps stood beside Abramović in front of 450 of their peers and shared their own personal experiences of Goldberg, then modeled the breathing exercise through which Abramović led the entire student audience. When she finished, the 55,000-square-foot Drill Hall was completely silent, and remained so during both the soundless preface and throughout Levit’s performance. Later, as students filed out, the Youth Corps gave each student a Guide to Unplugging, to explore how they could continue their experience outside of the Armory.

The Impact of Reflective Practice

We realized that unplugging is about being aware of your surroundings, reflecting on yourself, and being in control of who you are.

—Lizmarie, high school junior, Phase I Youth Corps

Although my co-teacher and I felt as though we had barely scratched the surface of reflective practice, the students still showed growth and articulated takeaways from their reflective experiences this semester.

From a quantitative standpoint, data gleaned from retrospective surveys show clear improvement in students’ skills in reflection: 80% of the students said that they reflected on their creative process and that their reflection influenced future choices more often than before they took part in the program. All of the students improved in developing the ability to communicate their ideas and/or find solutions through the creative process. Additionally, 100% also developed interpersonal skills through collaboration and leadership opportunities—closely aligned to the Youth Corps’ realization that reflecting and unplugging is not always a solitary activity, but often relates to our engagement with those around us.

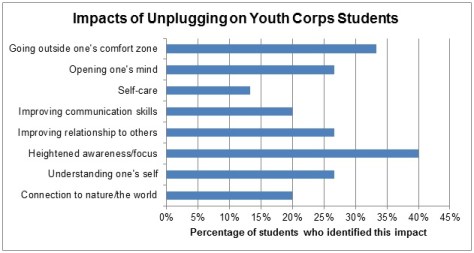

I also analyzed their written statements in the Guide to surface more specific themes about how the students felt the act of unplugging had affected them.

(Note: Percentages will not add up to 100%, since students’ statements often reflected more than one theme.)

In preparation for one of the sessions I am organizing at this year’s National Art Education Association Convention (see note above), I have been thinking a lot about what reflective practice is. The above impacts of “unplugging” identified by our students, are, I believe, all essential to reflective practice, no matter your age and whether or not you are consciously “unplugging” from daily stresses and technology.

Going outside of our comfort zones and opening our minds to new ideas and beliefs allow us to stay nimble, keep learning, and be empathetic. We must be conscious of how we communicate, and ensure we remain connected to the world—both physically aware of what’s around us and metaphorically, empathetic to others’ lives and backgrounds. Staying focused and aware of our surroundings and interactions allow us to be present in the moment. Overall, these practices help us understand ourselves better—both on a personal level and our relationship with others.

Applying Youth Takeaways to Museum Education Practice and Leadership

Be Present

When you stop thinking about everything else and just focus on what you’re doing, you gain a new experience. You are open to things.

—Joselin, high school junior, Phase II Youth Corps

With 40% of the Youth Corps identifying it as an impact of their time spent unplugging, it’s clear that being present is both an essential process in reflective practice and a benefit. In fact, as Terrelle put it, Abramović and Levit’s goal for Goldberg was “to place us outside our comfort zone and challenge us to be present to listen to the music. Marina and Igor wanted us to connect with our mind and body.”

In reflecting about how the semester went overall, my colleague/co-teacher, Pip Gengenbach, and I realized there was so much more we could have pushed the Youth Corps to try in exploring the idea not just of simply “unplugging,” but of truly being present. Of course, hindsight’s 20/20 and there is always room for improvement, but as I reread and analyzed the students’ writing, I found myself wishing we had facilitated even just one more session to encourage the students not to view being present as an end-game in and of itself, but to keep unpacking why the act is so important.

Even so, we scratched the surface: for example, when writing about paying attention rather than listening to music on her commute, Rachel said, “I realized how much more I was allowing myself to experience.” Leidy found presence in communicating more often with her family: “We express how we feel and look for a solution together.” Destiny models excellent self-care when describing her unplugging mechanism: “I put on a facial mask… close my eyes and center my mind on a blank space… I think of a state of peace and tranquility and allow my body to float.”

These experiences are all ways that we can practice being present in our professional lives. Setting aside a phone and committing not to email during a meeting with staff or colleagues, or during a program; taking time to look for solutions together, in person rather than via email; going for a walk during lunchtime—for that matter, actually taking a lunch; and taking time for self-care outside of work (I for one fully endorse Destiny’s masking regimen) are all small things we can do to be mindful with ourselves and when communicating with others.

Be Vulnerable

Often we feel the need to put up a wall. We don’t want people to see certain parts of us, so we hide. But … when we allow ourselves to be vulnerable, we open ourselves and our minds. This is how we begin to surrender to unplugging instead of fighting it.

—Sinaia, high school junior, Phase II Youth Corps

One of the most powerful ways that the Youth Corps—and we as educators—experienced vulnerability was through a two-hour workshop with vocalist and performance artist Helga Davis, mentioned above. Davis challenged us all to stare into each other’s eyes, in silence, for many minutes at a time. Cory describes what happened next:

We were then given the choice to come closer, go further away, or turn away from our partners. I personally chose to get closer to my partner because I wanted them to experience an awkward moment and adjust to it. I found myself visualizing my partner’s life line, and found it easy to see their comfort zone through their body language. My partner was fidgeting with their hands at first, but later on they adjusted. I also allowed them to look into my eyes without restrictions. I challenged myself to open up and dared myself not to worry about what they thought.

—Cory, high school junior, Phase I Youth Corps

Some members of Youth Corps, like Cory, have performance experience, and are used to participating in exercises similar to this one. They understood the intimate kinds of nonverbal communications that can occur. For others, myself included, the experience felt foreign and intimidating. Isatu wrote:

The purpose was to [try] to interpret who we are… I [was] afraid to reveal my true self to someone that I barely know. I felt like my partner was not looking at me, but looking into me: she seemed… more aware of herself than I was. The jealousy that I felt helped me to unlock myself, I let all the painful moments that I have experienced out through my tears, because whatever she saw in me made me free. Unplugging in this way helped me to feel the support of the people around me.

—Isatu, high school senior, Phase II Youth Corps

Isatu beautifully describes how allowing yourself to be vulnerable with another person can, in fact, help you both understand yourself better and connect on a deeper level with those around you. Understanding our strengths and weaknesses allows us to better understand our places in the world. Cory summarized her experience similarly: “We must be able to understand ourselves as a person first, in order to comprehend and change the things around us.”

This almost paradoxical statement directly relates to being an educator and leader. It goes back to the old airline oxygen mask adage (help yourself before helping others): know yourself in order to more deeply connect with others. After all, our jobs are not isolated: we have students, colleagues, and/or a field-wide network whom we not only support and encourage, but of whom we can ask support and encouragement. When we allow ourselves to be vulnerable in this way, we are able to foster empathetic collaboration that can strengthen our ideas and work.

I wholeheartedly endorse participating in something like this professionally, but perhaps more easily implementable and significantly less intimidating would be to try something like the Youth Corps’ mentor triads. During every Youth Corps program session, each education staff member works with a small group of two Youth Corps, where all members (staff included!) set a goal and hold each other accountable to it. Knowing that we were all equally committed and that we had a small group of people, most of whom we didn’t know well before our triads, who would be checking in on us are powerful incentives to keep on track. We meet for coffee or treats off-site, which made the whole experience seem special and important, but not a huge drain on busy schedules. And having a mixed group—one first-time student, one student who had been in the program already, and one adult educator—was an amazing way to stay fresh but also grounded. This would be easily replicable and powerful with groups of staff from different levels, areas, and even departments.

Challenge Yourself

Personally, I don’t like talking in front of crowds so I was really nervous. But Marina got us prepared by doing breathing exercises closely related to the Abramović Method, which helped me be less nervous… She made us feel like everything was fine and there wasn’t anything to worry about.

—Lizmarie, high school junior, Phase I Youth Corps

How many of us have created activities or goals that we know will challenge our students or visitors, yet perhaps don’t always “walk the talk” ourselves by participating alongside them, or trying something new in our own practice? You’re not alone! As I delved into ongoing reflection with the Youth Corps this semester, I was reminded that it is so important as an educator (and leader) to model taking up challenges, just as we expect our students to do, and to always be learning, never complacent.

Personally, I have been taking this to heart since starting at the Armory this past summer. After many years at art museums, I have been thoroughly enjoying the completely unconventional art we present here, as well as trying my hand at theater education techniques, the field from which several of my coworkers in the Education department come. Since last July, we’ve done role-playing, directed questioning, movement-based activities, “tinkering” with different materials—you name it, we’ve tried it. (And not to worry, we’re all learning from each other: I’ve been vehemently representing the “slow art” guard along the way.)

Although these techniques are certainly not unfamiliar to art museum educators, the fearless, try-anything, “show must go on!” attitude of unabashed risk-taking feels new to me, and is enormously inspiring. My own challenge for 2016 is to continue to reach—testing and stretching my own abilities as a teacher, and pushing our students in the process to do the same with their own goals and experiences in our programs. (And just in case you’re wondering, yes, my co-teacher Pip is part of my “mentor duo” to hold me accountable for this goal.)

Conclusion: Reflection and Self-Identity

I am grateful to Marina. I think what’s cool about her is that she does things that others are afraid to do. She’s taught me to always stand out.

—Terrelle, high school senior, Phase II Youth Corps

Awareness of self—of our strengths and our weaknesses, of our relation to others and to the world around us—is a key trait of leadership, no matter where in an organization’s hierarchy your job may place you. Understanding our own identity, through reflective practice, allows us to better understand our own work, how we teach, and the place of our institution and programs in our students’ or visitors’ lives.

Youth are in a key phase of their life where they themselves are testing out and defining who they are as people—their interests, beliefs, connections, and communities. But as we all know, it’s not only youth who use museums and cultural institutions as spaces for meaning-making and self-understanding or reflection; visitors of all ages and backgrounds do the same. And it’s important to remember that we ourselves as educators participate in this process as well, every time we reflect on our teaching practice, on our role as leaders in our institutions, or as participants in the world. Being conscious of the reflective process—being present in it, if you will—allows us to be intentional about our teaching practice, improve our connections with our audiences, and ultimately create experiences for all that bring our institutions more deeply into our visitors’ lives.

Header Photo: Lizmarie, high school junior and Phase I Youth Corps, speaks to NYC public school students alongside Marina Abramović and fellow Youth Corps. Photo by Da Ping Luo

5.

5.  4.

4.  3.

3.  2.

2.  1.

1.