By Clare Hagan, DeWitt Clinton High School

During most days here in New York (and especially the recent spring break), art museums are thronged with families. Parents, grandparents and their children of all ages orient themselves with maps, cruise galleries and favor an exhibit or two leaning in to read labels, manipulate interactives, ask questions and make observations together. They’ve come to be entertained, spend time together and invest in the value of informal education.

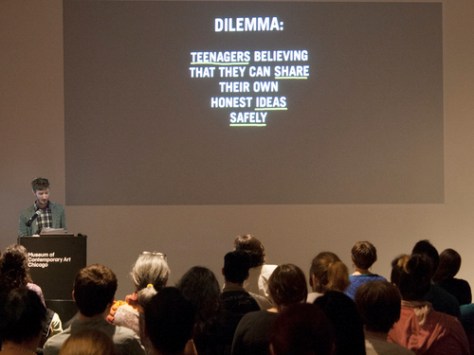

As most of us know, families build a foundation for behavior and learning strategies and research indicates that family museum visits lead to adults who find value and comfort in museums. So what happens when children are marginalized because they don’t visit museums with their families? How might they feel comfortable and find value in a museum? While museums turn to more inclusive programs, policies, and exhibits in order to reach more families, what can the individual classroom teacher do to help create lifelong museum visitors?

I am an English teacher at DeWitt Clinton High School, a large public high school in the Bronx. My school currently serves 2,745 students of which 76% receive free lunch and 21% are English Language Learners. Our total population is comprised of 62% Hispanic, 29% Black, 7% Asian, and 3% other. With the average museum visitor being white, college educated, and affluent, my students are certainly in the minority. On top of that, due to budget cuts and the growing focus on test scores, schools like ours are taking fewer and fewer field trips.

At the beginning of the year, 83% of my students claim to have never visited an art museum. Nevertheless, after their second field trip, 96% say they are “likely” or “very likely” to return to one. As I look at these results, I try to understand what makes this class work.

Exploring Museums as Cultural and Community Resources

During their senior year, students can elect to take my year-long Humanities class for English credit. As in most humanities classes, my students learn about a long line of classical texts and objects but in my class they also learn about critical issues related to the people and institutions that preserve, shape, and disseminate cultural knowledge. They analyze intentional learning communities from ancient libraries to contemporary museums to the internet through texts ranging from historical records to reviews of current exhibits. They ask:

- Whose culture is being preserved and how is it represented?

- Where are the silences and why might they persist?

- What are the criteria for a good collection or exhibit?

- How are informal learning spaces different from formal education? How are they the same?

In response, their mid-year project is to propose a museum exhibit on a subject of their choice and their year-end assignment is to design a public humanities project for their own community. Even if all my students don’t become museum curators and cultural events planners, at the very least they know that they can critically engage in public dialogue about cultural heritage, encounter deep experiences with works of art, and participate in self-directed learning in museums.

From day one, my students are engaged in object-based lessons. They read curatorial essays and look at several objects on a weekly basis, mostly from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. By focusing on the Met as a primary resource, my students come to understand it deeply as a public institution. At the same time, they focus on works of art in depth. Based on my studies with educational philosopher Maxine Greene and through professional development at the Lincoln Center Institute, I have learned to infuse my classroom with aesthetic education practices.

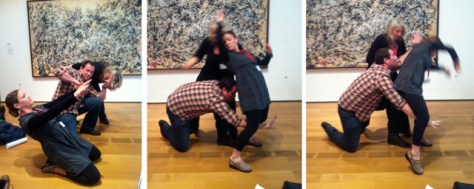

A typical lesson in my classroom involves students in a combination of deep noticing, embodied experiences, play, analysis, discussion, art making, questioning, researching, making connections, and meta-cognitive reflection. Together we wonder about why art matters, why history matters, how both get made, and how both get preserved. In addition, my students learn how to approach an object. In the classroom, groups lean in to an image on an iPad or stand back and discuss an image projected on the wall. They look at the object first and annotate the label second. They learn to look together as well as individually, to listen for their curiosities, find comfort with ambiguity, and to follow through with informal research.

By late fall we are ready for our first self-guided tour and we visit the Met’s Greek Art galleries. It didn’t take long for me to learn that students need preparation for male nudity in theses galleries, so in the days prior to our visit we look closely at nudity and consider its role in ancient Greek culture. This way their field of vision goes beyond the nudity and they can see these objects from multiple perspectives. At the museum, students look at a few pre-selected objects making connections to our study of Homer’s The Odyssey. Next, they explore the galleries in pairs looking for patterns in order to draw conclusions about motifs. Finally, students are encouraged to explore independently and gravitate toward one object which they will eventually research and write about. After our trip, we reflect on our visit and share our research.

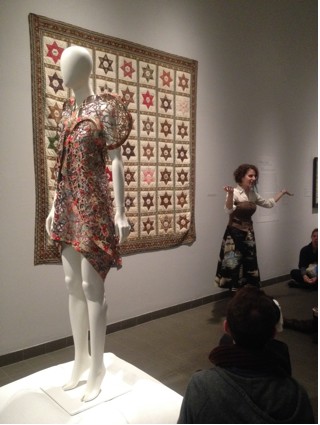

In the spring, we return to the Met for a second visit, this time to experience the Islamic Art galleries. My students are noticeably more comfortable during this visit and are able to take on an additional assignment. This assignment asks students to use photography to develop intimate engagement as well as critical distance. Each student is asked to submit four distinct shots: an architectural detail, a fleeting moment, a close up of an object (one they will also research), and a selfie. Upon returning to the classroom we view our collection of photographs, share our research, and reflect on the visit as seen through our own eyes.

Creating Deep Connections with Museums

When students visit museums, they gain experiences and build knowledge. As teachers and museum educators, we often activate schema before, during, or after experiencing a particular object or exhibit in order to make meaning. We do this to help students make connections. But the schema that experienced museum visitors activate is not only related to the content of objects and exhibits. It’s about what to expect from a museum visit and how to make the most of it. How to lean in and look deeply, how to explore independently and together, how to listen to and follow our curiosities. Even how to play or to take a critical stance.

When students don’t visit museums with their families they need classroom teachers to introduce them to the inroads of experiencing one. Otherwise they might never feel welcome or even inclined to try a visit. From my experience, curriculum and lessons based on aesthetic education practices that also familiarize students with museums as a resource need to happen through repetition over an extended period of time, spiraling throughout the course of a semester or a year. This is possible when teachers choose one museum to focus on using objects and text related to their collections. I also believe that teachers need to layer their curriculum with a range of critical questions and projects related to the sources of our cultural heritage. By becoming aware of the ways our cultural heritage is shaped and disseminated, students are empowered and see themselves as active participants in cultural dialogue.

Where else can we find success in reaching marginalized youth and what other roles can classroom teachers play? And finally, how can more teachers be persuaded to create deep connections with museums?

About the Author

CLARE HAGAN: Humanities teacher at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, NY. At DeWitt Clinton, Clare has developed and implemented curriculum based on museums as a resource, museums as an object of study, aesthetic education and object-based lessons. She has presented her Humanities curriculum at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and has conducted professional development workshops on object-based lessons. In addition to her MA in English Education from Teachers College, Columbia University, she has studied critical issues in museum education at Teachers College and aesthetic education at Lincoln Center Institute. Currently, through generous funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, she is studying Islamic verse and will be publishing her museum infused curriculum online this summer. Clare’s postings on this site are her own and don’t necessarily represent DeWitt Clinton High School’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

CLARE HAGAN: Humanities teacher at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, NY. At DeWitt Clinton, Clare has developed and implemented curriculum based on museums as a resource, museums as an object of study, aesthetic education and object-based lessons. She has presented her Humanities curriculum at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and has conducted professional development workshops on object-based lessons. In addition to her MA in English Education from Teachers College, Columbia University, she has studied critical issues in museum education at Teachers College and aesthetic education at Lincoln Center Institute. Currently, through generous funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, she is studying Islamic verse and will be publishing her museum infused curriculum online this summer. Clare’s postings on this site are her own and don’t necessarily represent DeWitt Clinton High School’s positions, strategies, or opinions.