For the past two decades, the overall discourse regarding Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) has been the subject of rather thorny debate. The often-cited conversation between Philip Yenawine and Danielle Rice at the 1999 National Docent Symposium (published in 2002) productively drew out many of the disagreements about the role of information in museum teaching, especially with beginning viewers and first-time museum visitors. In their recent book Teaching in the Art Museum, Rika Burnham and Elliot Kai-Kee frame VTS as a restrictive teaching method, wondering about participants’ experience in the galleries: “Have they not perhaps been cheated out of an authentic encounter with the painting?” These debates continue to today, and, at times, it seems like one needs to draw a line in the sand and decide which side they stand on.

For the past two decades, the overall discourse regarding Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) has been the subject of rather thorny debate. The often-cited conversation between Philip Yenawine and Danielle Rice at the 1999 National Docent Symposium (published in 2002) productively drew out many of the disagreements about the role of information in museum teaching, especially with beginning viewers and first-time museum visitors. In their recent book Teaching in the Art Museum, Rika Burnham and Elliot Kai-Kee frame VTS as a restrictive teaching method, wondering about participants’ experience in the galleries: “Have they not perhaps been cheated out of an authentic encounter with the painting?” These debates continue to today, and, at times, it seems like one needs to draw a line in the sand and decide which side they stand on.

So what is VTS?

For those of you unfamiliar with Visual Thinking Strategies, it is an inquiry-based teaching method developed by Abigail Housen and Philip Yenawine more than twenty years ago and used in museums and school classrooms across the country. Here is how Philip Yenawine describes it in his latest book Visual Thinking Strategies: Using Art to Deepen Learning Across School Disciplines (2013):

“VTS uses art to teach visual literacy, thinking, and communication skills—listening and expressing oneself. Growth is stimulated by several things: looking at art of increasing complexity, answering developmentally based questions, and participating in peer group discussions carefully facilitated by teachers.” (19)

Even those who do not practice VTS may be familiar with the sequence of open-ended questions that form one of the main aspects of VTS teaching practice:

- What’s going on in this picture?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What more can we find?

If you are interested in learning more about VTS, the foundational research behind it, and ongoing research in museums and classrooms today, here are some excellent resources:

- Visual Thinking Strategies website includes a “Research” section where you can download and read several research reports, articles, and case studies about VTS theory and practice.

- The Milwaukee Art Museum provides an excellent overview of VTS, with teaching tips and videos to help teachers begin to implement the basics of this strategy in their own classroom.

- One of the leading museums implementing VTS theory and practice in the galleries is the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and their website includes research reports and an article written for the Journal of Museum Education.

Pushing Beyond the Protocol

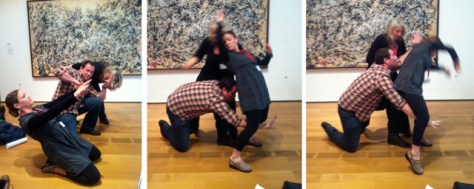

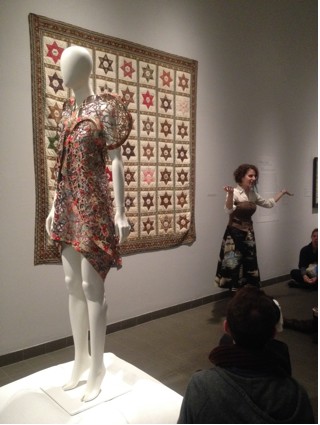

My own approach toward VTS has been to set aside any controversy and more fully explore the research as well as the practical implementation of these teaching strategies ‘on the ground’ in museums. Back in 2009, I led a panel at the American Association of Museums conference that called attention to the many questions, challenges, and apprehensions that exist regarding this method. After interviews with more than 30 museum educators from across the country, I was able to gain a more complete and complex view of how VTS (and the research behind it) is being implemented in art museums—including adaptations of the original protocol, metacognitive dimenions as part of the VTS experience, pushing the boundaries of artwork selection, and alternative applications for docent and teacher training. I have even found institutions that use Abigail Housen’s “stages of aesthetic development” (the core foundation of VTS) as part of their curatorial practice, the writing of labels and wall texts, and working with teaching artists to examine ways of creating art that addresses developmental stages of the viewers. In addition to being one of the most commonly used teaching methods in art museums today, it is interesting to see how many other ways that VTS and its research has entered into museum practice.

Burning Questions about VTS: Ask Philip Yenawine

While I have never been trained in VTS myself, I have adopted it as part of my own teaching toolbox — often using its open-ended questions as a way to spark looking, talking, and listening with a work of art. I respect the research and practice involved with VTS, which is why I jumped at the chance to partner with the national VTS organization to bring Philip Yenawine here to the Portland Art Museum. Philip has been traveling around the country since his latest book was released last year, and his speaking engagement here at the Portland Art Museum (this Saturday, May 3rd, 2:00pm) will be part of that series of talks.

While I have never been trained in VTS myself, I have adopted it as part of my own teaching toolbox — often using its open-ended questions as a way to spark looking, talking, and listening with a work of art. I respect the research and practice involved with VTS, which is why I jumped at the chance to partner with the national VTS organization to bring Philip Yenawine here to the Portland Art Museum. Philip has been traveling around the country since his latest book was released last year, and his speaking engagement here at the Portland Art Museum (this Saturday, May 3rd, 2:00pm) will be part of that series of talks.

When we were first offered to host Philip’s talk here in Portland, I invited Philip to also join me for a conversation on stage as part of this Saturday’s program (which he gladly accepted). I wanted to have the opportunity to discuss the applications of VTS with art museum teaching, and discuss some of the ‘burning questions’ that many museum educators have about VTS research and practice.

So, I am using this blog post (and the ArtMuseumTeaching community) to gather some juicy, burning questions that we all might have about VTS in museum teaching. To seed this “open think” process of gathering your questions, I asked Jennifer DePrizio and Michelle Grohe at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston (a leading museum in VTS research & practice) to send me some of their questions. Here is some of what they sent me:

- We know a lot about what VTS looks like (both in terms of facilitation and types of learning to expect) in elementary students, primarily in grades 3-5. What does that learning and teaching look like with older students, particularly high school?

- Listening is the cornerstone of paraphrasing and ensuring that students know that you not only listened to their ideas, but they were heard as well. That can be a difficult skill to encourage teachers to develop. Can you really train someone to be a good listener? How can we design effective professional development experiences that help teachers become aware of how they listen, and how to listen better? What activities and practice can we put into place to help our gallery educators hone their listening skills?

- Since professional development programs at the Gardner invest a lot of time, over time, with teachers, what does their growth look like in terms of: aesthetic development, comfort with visual art, use of student-centered teaching practices, use of VTS questions with non-visual art, overall attitudes and understandings of teaching and learning and role of visual art in the classroom/school?

- What is the long-term effect or stickiness for VTS?

- What does the use of VTS look like with non-beginners, or with viewers who are moving from beginner viewers (Housen stages I and II), into different aesthetic stages such as Housen’s stage II/III, II/IV and III? How could we best support their growth while also challenging the students effectively? What would that facilitation look like? How would we know that we were addressing the students’ actual questions, not just sharing information that we think would help them?

- How do we responsibly respond to the many misrepresentations of VTS that exist? How do we help colleagues in the field of art museum education understand the nuances that are available within VTS?

ADD YOUR QUESTIONS:

Please help me crowd-source some more ‘burning questions’ about VTS, and use the Comments area below to add your own questions. If you add your thoughts here between now and Saturday, I’ll bring many of these questions to my conversation with Philip Yenawine here at the Portland Art Museum (and I should be able to post the video of this conversation here next week).

Thanks for helping me think about VTS in this open space for exchange, questions, and ideas! And I’m looking forward to my conversation with Philip on Saturday (join us if you’re in Portland — the event is FREE and starts at the Portland Art Museum at 2pm).