Written by Andrea de Pascual

Invisible Pedagogies (IP) is a collective that works on the creation of a space in which we can rethink the relationship between art and education. It was born in Madrid in 2009 and was formed by educators from different areas such as high schools, colleges, community contexts, and art centers. It was created of the need we felt to look for new ways of thinking about the theory and practice in art education. We met while taking a doctorate course entitled Didactics of Suspicion, whose professor, Maria Acaso, is now the director of most of our doctorate studies. A strong bond was created between us, and it still helps us to become stronger in our struggle against the establishment. We were born as a “self-doctorate” (self taught) group who deals with theory but because of our methodological nature, yet based upon action-research strategies, we were soon forced into practice.

Invisible Pedagogies (IP) is a collective that works on the creation of a space in which we can rethink the relationship between art and education. It was born in Madrid in 2009 and was formed by educators from different areas such as high schools, colleges, community contexts, and art centers. It was created of the need we felt to look for new ways of thinking about the theory and practice in art education. We met while taking a doctorate course entitled Didactics of Suspicion, whose professor, Maria Acaso, is now the director of most of our doctorate studies. A strong bond was created between us, and it still helps us to become stronger in our struggle against the establishment. We were born as a “self-doctorate” (self taught) group who deals with theory but because of our methodological nature, yet based upon action-research strategies, we were soon forced into practice.

On the other hand, invisible pedagogies is a concept that already existed before the collective, exploring education beyond the boundaries of the curriculum and considering pedagogical elements that hadn’t been addressed in the learning-teaching experience until now. Invisible pedagogies is the reflection upon the non-explicit micro-discourses that all-together form the macro-discourse that is the pedagogical act. And although they remain on a second level, they are likely to transform the body and soul of the participants involved in it.

In other words, the teaching act is a mediated performance in the same way that a theatrical performance is mediated and its different elements (micro-discourses) will make up a pedagogical narrative. What do our students in class, the participants in a workshop, or museum visitors learn beyond the contents we have prepared for them? An example we always use to explain invisible pedagogies is the door. What is the meaning of closing a door in the classroom? And of leaving it open? Or asking the students which they prefer? In a museum the fact that the entrance doors are automatic or revolving or that one must push them, will send a specifically different message to the visitor and will affect the way he or she interacts with the art inside.

“Invisible pedagogies have many ways of changing people in their participation in the educative act. They help them to learn or not; they get people to become passionate for knowledge or deadly bored, they make them feel fear or pleasure, they invite them to share or to hide” (Acaso, 2012)

Invisible Pedagogies in Museums

We do not limit ourselves to making invisible pedagogies visible, but, once we have detected them, we analyze and transform them by applying them in new contexts and using new educational theories in different projects.

In the case of the three educators in the Invisisble Pedagogies (IP) collective that work in museums and art centers (Eva Morales, David Lanau and myself, Andrea De Pascual), rather than changing doors, we are offering whole new formats that expand the concept of education in museums. Little by little, museums and art centers are changing their attitudes and are opening their minds to new educative proposals which go beyond guided tours, audioguides, or workshops out of the exhibition spaces. However, the real opportunity for us came from Matadero Madrid.

As a contemporary art center, Matadero Madrid does not have an education department as such, but it does have great interest in educative aspects far beyond offering the heritage of the institution as an educational resource available for schools to complete their curriculums, or the simplification of the contents of curatorial work. This institution gave us the possibility to design our educative actions from an approach which Carmen Mörsch calls transformative discourse:

“Practices related to this discourse (transformative) work against the categorical or hierarchical differentiation between curatorial effort and gallery education. In this practice, gallery educators and the public not only work together to uncover institutional mechanisms, but also to improve and expand them” (Mörsch, 2009)

Working for Matadero Madrid helped us to visualize the (post)museum more as “a process or experience not a building to be visited. In it the role of the exhibition is to be focus for a plethora of transient activities” (Hooper-Greenhill, 2000). And it helped us see education as “an element of ongoing personal growth, that is not limited to one particular stage of life. Education as play, a way of unravelling the media theatre. Education as an open source operating system that turns us into critical citizens. Education as a game played by all individuals, from all eras. Education as a utopia for a culture-sharing society” (Zemos98, 2012).

These are just a few of our references that helps us to transform directionality, format, and methodology (among other aspects of traditional museum education) when designing our educational actions.

Transforming Invisible Pedagogies

I will present now some of the invisible pedagogies we have detected, analyzed, and transformed during the almost 5 years we have been working together, as well as issues and goals that are part of our methodological frame.

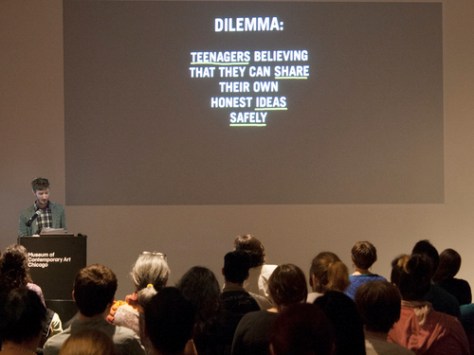

One of the most important discourses we want to change is the power-knowledge barrier built between educators (visible voice of the institution during the praxis of museum education) and participants (individuals that in most cases feel they don’t have anything to say about contemporary art). In order to change this invisible directionality, we think that just sitting in a circle or introducing ourselves at the beginning of an activity (strategies that are already common practice) is not enough. One of our strategies to change that invisible pedagogy is to have always more than one educator per workshop. The idea is not only to decentralize people’s attention, so as not to have a single point of view, but also to show that among the “agents of the institution” there can be disagreements and even discords. It is a scheme to make the one true voice disappear in favor of a multiplicity of voices, all of them being equally valid. We also think that it was fundamental, in order to bring down this wall of conventional teaching, to introduce analytic dialogue (based on the possibility instead of the agreement) and open-ended activities receptive to the unexpected.

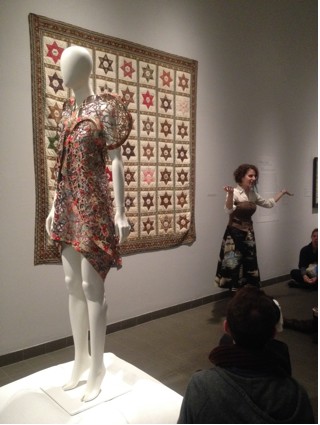

Another important invisible discourse we have to dismantle and transform is that Art and Education are two separate things. Art and Education are the two sides of the museum coin and should be approached at the same time. Just as art can be educative, education can be artistic. Why not use performance, installation, minimalism, video, body action. etc. as educative tools? We’re interested in the idea of using contemporary art not only as content of the program but also as a pedagogical format.

I think that nowadays we, museum educators, will in most cases agree that participants in our programs produce knowledge and add meaning to the exhibits but are we really honest? Are we prepared to believe it? What are we really telling our participants? If we want the museum to be a social agent and a place of action and transformation, we need to consider the participants in our actions as learning-communities capable of producing knowledge of the same quality, interest, and authenticity as the knowledge produced by artists and curators. To make this more than a statement, we never use a separate space in the museum (like a workshop reserved for education activities) and we find strategies through which participants and visitors can leave a footprint in the gallery or the museum. We mean to use the galleries, halls, atriums, or even the patios of museums as learning sites. We think of the museum as a learning laboratory in which new layers of knowledge are added to the pre-existing ones by the visualization of the knowledge production of the participants.

Last but not least, we introduce the action-research tool in museum education to change the invisible discourse that exists inside institutions around education departments. Although education departments in museums are now common and have their importance, the untold truth is that they still don’t have the resources or the tools needed to reach the status they deserve within the institution. Research is essential to change this dynamic. First, because the knowledge and research produced in museum education departments should be available to specialists; therefore archives are just as indispensable in education departments as in those of curatorship. Second, because in education there is no way of knowing how to improve the practice if you don’t analyze it.

IP Museum Projects at Matadero Madrid

The first time IP worked with Matadero Madrid we developed a family workshop program that we called En Construcción. Disculpen las molestias (Under construction, sorry for the inconvenience) to activate a gallery dedicated to contemporary art called Abierto X Obras (Open for Repairs). IP transformed the family workshop format into intergenerational workshops, or, as we called them on that occasion, 0-99 workshops (from 0 to 99 years of age). The goal was to create a more inclusive format in which teenagers or babies could participate, or in which family was extended to include roommates, close friends, or even to allow adults (alone or accompanied with or without children) and to have them all participate in active way.

For our second project, we were invited to strengthen and activate the relationships between the audience and the art production that was taking place in El Ranchito — an exhibition that made visible the working processes of artists rather than the finished work. The project was called Espacio Visible (Visible Space), and it was literally a space inside the gallery available to educators and visitors to add meaning to the exhibition through their own contributions.

Our third project called Here, together now: Building art communities in a changing world, was a multi-national collaborative project to rethink how an art exhibition is produced, with and for whom. The three members of IP Museums were artists-educators in residence invited to create a scenario of mediation where the public could relate with what was being done.

In 2013 and 2014, we are developing the project Microondas: Recalentando la educación (Microwave: reheating the education) that consists of a collaborative-research and action group that rethinks current educational methodologies within new activist frameworks and theories. Our last seminar was called “Activist (?) Pedagogies”.

Opening the Conversation

Can you detect other invisible pedagogies in museum education? How would you transform them to change the dynamics of teaching in the museum? By incorporating invisible pedagogies in the practice of museum education, in what ways do you think they could expand the concept of education within the museum? Add your voice to the conversation below, or on Twitter with hashtag #invisiblepedagogies.

About the Author

ANDREA DE PASCUAL: A bilingual (Spanish-English) education specialist, artist, and researcher, Andrea is founding member of the collective Invisible Pedagogies and creator of the project The Rhizomatic Museum. She has worked for the past 8 years in a variety of museums, cultural institutions, and praxis collectives. Her work has focused on how the museum can be activated not only as a site for individualized contemplation, but also as a community-based site where knowledge is shared, and social, political and environmental issues are addressed. Andrea graduated from the Masters Program in Art Education at New York University in 2013 while on a Fulbright Fellowship, in connection with her Doctoral work as a candidate in Art Education in Museums at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Her dissertation is titled “Non Hierarchic Knowledge Production Strategies Within Western Visual Art Museums: The Rhizomatic Museum.” Andrea’s postings on this site are her own.

ANDREA DE PASCUAL: A bilingual (Spanish-English) education specialist, artist, and researcher, Andrea is founding member of the collective Invisible Pedagogies and creator of the project The Rhizomatic Museum. She has worked for the past 8 years in a variety of museums, cultural institutions, and praxis collectives. Her work has focused on how the museum can be activated not only as a site for individualized contemplation, but also as a community-based site where knowledge is shared, and social, political and environmental issues are addressed. Andrea graduated from the Masters Program in Art Education at New York University in 2013 while on a Fulbright Fellowship, in connection with her Doctoral work as a candidate in Art Education in Museums at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Her dissertation is titled “Non Hierarchic Knowledge Production Strategies Within Western Visual Art Museums: The Rhizomatic Museum.” Andrea’s postings on this site are her own.