Written by Jessica Kay Ruhle

“By looking at the art we can talk about topics that people don’t usually like to talk about.” – Rumaisha Tasnim

“Each viewer sees the art. What you see in it is your truth, it doesn’t have to be my truth.” – Kelsey Trollinger

Recent high school graduates Rumaisha and Kelsey spent much of the past two years at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. As original members of the Nasher Teen Council (NTC), they led public programs, installed exhibitions, met artists, and created their own art. Their quotes are from artist talks they gave this month at an exhibition of work by the teens at a downtown gallery. Paintings and collages from the exhibition Nina Chanel Abney: Royal Flush inspired much of their work.

As they spoke about the power of art to encourage meaningful conversations and validate individual experiences, Rumaisha and Kelsey–along with the other council members–joined their voices with countless other leaders who recognize the critical role art plays in civic discourse and the growth of a community. During times of uncertainty, political upheaval, and protest, we have to seek out these voices, both past and present, which celebrate what we know to be true about the critical need for influential artists and art institutions.

John F. Kennedy, a powerful champion for the arts, stated, “I see little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than the full recognition of the place of the artist.” His message, from over fifty years ago, still offers inspiration and leadership on the political role of art in a democratic society.

In a 1963 speech from Amherst College given in honor of Robert Frost, Kennedy begins with praise for the role of universities and an important reminder that “with privilege goes responsibility.” He asks the listener, “What good is a private college or university unless it’s serving a great national purpose?” He insists that the benefits and pleasures of an academic institution are not merely for the graduates to achieve individual economic advantage. Instead, he argues, the cultural agreement is that graduates must use their advantages for the public interest.

After reminding universities of their cultural obligations, Kennedy praises Frost and his poetry. More broadly, he celebrates art as a democratic institution and applauds artists as foundational to America’s greatness. He states, “For art establishes the basic human truths which must serve as the touchstone of our judgment. The artist [. . .] becomes the last champion of the individual mind and sensibility against an intrusive society and an officious state.” Rather than considering artists “who question power” a threat, he welcomes their critiques as “indispensable.”

Nina Chanel Abney critically examines the world through her body of work and requires the same of her viewers. Nina Chanel Abney: Royal Flush, her first solo museum exhibition, addresses politics, celebrity gossip, race, gender, power, and more. In it, Abney spotlights some of the most heated topics in American culture and boldly holds accountable those who misuse their power.

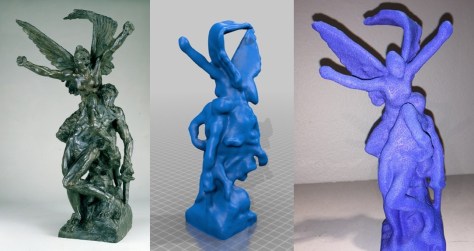

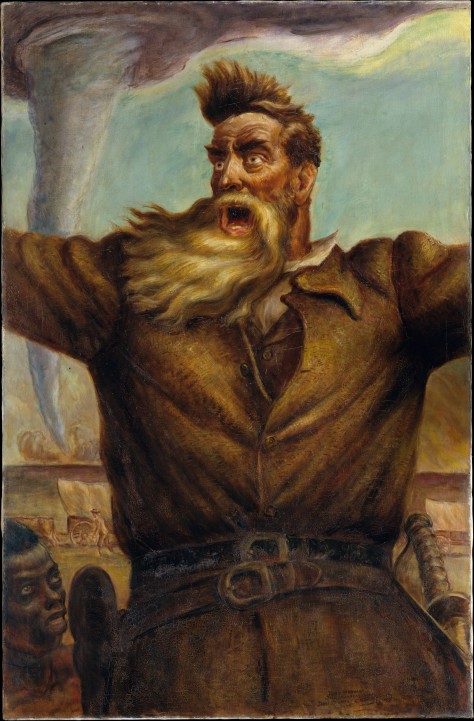

In The Boardroom, 2008, the nearly naked, sometimes bleeding bodies represent the financial leaders who valued profit over stability and led to economic collapse. Either depicted as clowns or wearing yellow gloves that allow them to keep their hands clean from their dirty work, Abney literally strips these men of the power and prestige often afforded to them by their business suits and corner offices.

Six years later, in a more abstracted and digital style, Abney turns her critical eye towards the issues of race, gun violence, and police brutality in the piece UNTITLED (FUCK T*E *OP), 2014. While her geometric “emojification” of this work differs greatly from the painterly style of The Boardroom and other earlier works, Abney still uses her platform to question societal power structures.

In his Amherst speech, JFK states, “the highest duty of [. . .] the artist is to remain true to himself and to let the chips fall where they may. In serving his vision of the truth, the artist best serves his nation.” Abney echoes his voice in more contemporary language saying, “I like to just drop the bomb and start the conversation and then leave out the room.”

The gallery conversations that Abney starts with UNTITLED (FUCK T*E *OP) often include visitor descriptions of the scene as chaotic and confusing. As viewers examine the painting, patterns emerge. Visitors identify elements that remind them of pinball machines, streetlights, and the visual noise of cable news channels, the internet, and New York’s Times Square. Visitors consider her use of language. Viewers may read the simplified language, such as “POW” and “YO”, as references to digital culture and the abbreviated communications of texts and tweets. The discussion frequently shifts to Abney’s use of the “X” symbol in this piece and questions of who is a target, who is silenced, and who has a voice. Reading “FUCK T*E *OP” in the top left corner of this painting, conversations may include what language is, and is not, censored, both in her work and, more broadly, in society.

As a leading voice, Abney opens up the conversation to everybody by sharing her visual vocabulary without fully translating the meaning. Remaining intentionally ambiguous about her work, she encourages others to bring their life experiences to their viewing of the truths she depicts and create their own interpretations.

Abney’s examination of societal power structures and contemporary digital culture continues with the most recent painting in the exhibition, Catfish, 2017. Abney says of this piece, “I feel like I am combining everything here.” A monumental portrait of selfie culture, Catfish depicts provocatively positioned female figures who meet the viewer’s gaze directly and self-assuredly. Surrounding the women are dollar signs, many of Abney’s “X” symbols, and language that again reflects the brevity of the digital world. Whatever assumptions a visitor first makes about these women are questioned by the Catfish title. The term “catfish” suggests the bottom-feeding fish, as well as the practice of misrepresenting oneself online, often for financial gain. With this painting, Abney simultaneously incorporates the aesthetic of digital culture and questions how representations of self are used, or misused, within that culture.

At a time when many political and economic leaders ignore the responsibilities of privilege and dismiss the need for critical voices, artists and institutions can turn to the words of JFK for encouragement and guidance and to the contemporary artists, like Abney, doing the important work of examining societal structures. Emerging artists, like Rumaisha and Kelsey, are also adding their voices to the dialogue. They will continue the work of JFK and Abney, as well as shape the conversation in ways we cannot yet imagine.

To end his speech, JFK shares his hope for the arts saying, “I look forward to an America which will steadily raise the standards of artistic accomplishment and which will steadily enlarge cultural opportunities for all of our citizens.” Fortunately, in many places, that America has arrived. It is imperative that we continue to seek new voices – historic and contemporary, spoken and visual – to lead the continued march forward and together.

What voices – established or emerging – are leading you today?

Additional Information:

More about JFK’s 1963 speech at Amherst College –

https://www.amherst.edu/library/archives/exhibitions/kennedy/documents

https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/05/01/jfk-amherst-speech/

More about Nina Chanel Abney –

More photos from the Nasher Teen Council exhibition In Our Own Worlds –

https://www.flickr.com/photos/nashermuseum/albums/72157684473570616

Nina Chanel Abney: Royal Flush, is at the Nasher Museum through July 16, 2017. After that, it will travel to multiple locations. Go check it out!

- Chicago Cultural Center: February 10 – May 6, 2018

- The Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles: September 23, 2018 – January 20, 2019

- Neuberger Museum of Art, SUNY, Purchase: April 7 – August 4, 2019

* * *

About the Author

JESSICA RUHLE is Director of Education & Public Programs at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. Jessica has worked at the Nasher Museum since 2010. Previously, Jessica worked at the North Carolina Museum of History, the North Carolina Museum of Art, and Marbles Kids Museum. Before arriving in North Carolina, she worked at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Jessica has an MAT in Museum Education from The George Washington University, as well as a BA in Art History from Davidson College. Jessica’s postings on this site are her own and do not necessarily represent the Nasher Museum of Art’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

JESSICA RUHLE is Director of Education & Public Programs at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. Jessica has worked at the Nasher Museum since 2010. Previously, Jessica worked at the North Carolina Museum of History, the North Carolina Museum of Art, and Marbles Kids Museum. Before arriving in North Carolina, she worked at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Jessica has an MAT in Museum Education from The George Washington University, as well as a BA in Art History from Davidson College. Jessica’s postings on this site are her own and do not necessarily represent the Nasher Museum of Art’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

* * *

Header Image: Ayubi Kokayi, NTC member, performs spoken word in front of The Boardroom, 2008, photo by J Caldwell.

DANIELLE CARTER is a freelance museum educator and researcher based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She studied Art, Art History, and Museum Studies (2013) at Florida State University before moving to the Netherlands to pursue her Master’s degree in Arts and Heritage: Policy, Management, and Education (2015) at Maastricht University. Through her experiences as an arts and museum educator in the United States and abroad, she has become interested in the museum (learning) experience, the narrative of the museum (learning) experience, interactions between visitors and museum objects, the mediatory role of the museum, and play in the museum space. In Amsterdam, she bikes, takes advantage of the sun every time it comes out, and falls in love with every dog that she sees. To find out more about Danielle’s activities, visit her website (

DANIELLE CARTER is a freelance museum educator and researcher based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. She studied Art, Art History, and Museum Studies (2013) at Florida State University before moving to the Netherlands to pursue her Master’s degree in Arts and Heritage: Policy, Management, and Education (2015) at Maastricht University. Through her experiences as an arts and museum educator in the United States and abroad, she has become interested in the museum (learning) experience, the narrative of the museum (learning) experience, interactions between visitors and museum objects, the mediatory role of the museum, and play in the museum space. In Amsterdam, she bikes, takes advantage of the sun every time it comes out, and falls in love with every dog that she sees. To find out more about Danielle’s activities, visit her website (

HOLLY GILLETTE is an art museum educator with an interest in gallery teaching and community building. She is currently an Education Coordinator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) where she oversees the school and community partnership program Art Programs with the Community: LACMA On-Site. Prior to working at LACMA, she began her career in Museum Education at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, CA, focusing on school, early childhood, and family audiences. Holly holds a MS.Ed. in leadership in museum education from the Bank Street College Graduate School of Education and a B.A. in art history and studio art from University of California, Davis. Holly’s postings are her own and don’t necessarily represent LACMA’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

HOLLY GILLETTE is an art museum educator with an interest in gallery teaching and community building. She is currently an Education Coordinator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) where she oversees the school and community partnership program Art Programs with the Community: LACMA On-Site. Prior to working at LACMA, she began her career in Museum Education at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, CA, focusing on school, early childhood, and family audiences. Holly holds a MS.Ed. in leadership in museum education from the Bank Street College Graduate School of Education and a B.A. in art history and studio art from University of California, Davis. Holly’s postings are her own and don’t necessarily represent LACMA’s positions, strategies, or opinions.

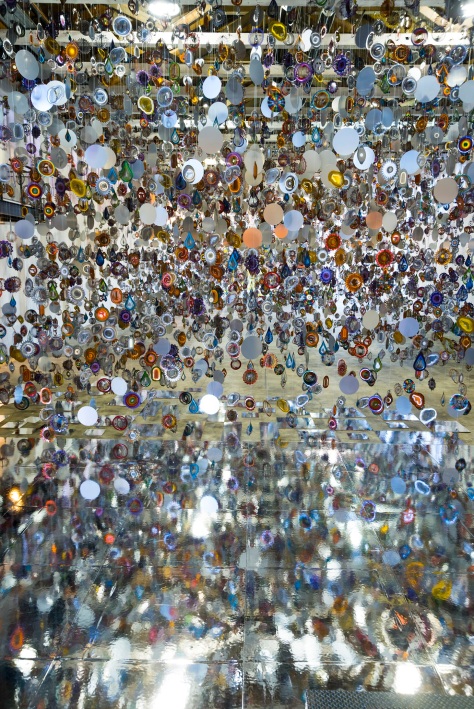

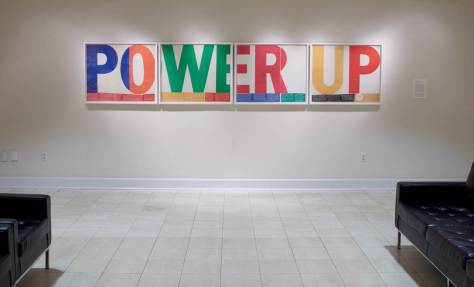

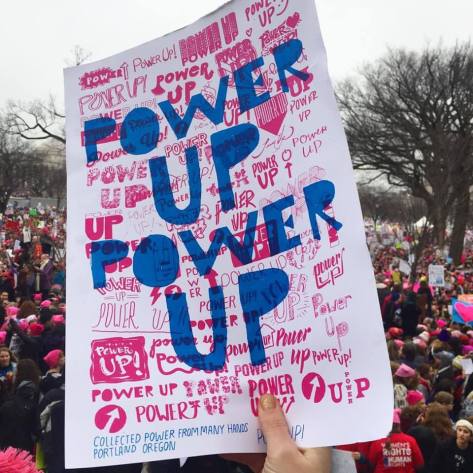

When we visit an art museum, deep down inside, we’re largely seeking out creativity, beauty, joy, energy, strength, connection, even love. When we stand in front of a work of art, perhaps we’re even looking to connect with something bigger than ourselves. Corita Kent brought all of that to the museum and our community in powerful ways. Having her work on view here at the museum and seeing its deep transformative effect, I am drawn to reflect on how the power of art does spread out to a community and beyond the walls of a museum.

When we visit an art museum, deep down inside, we’re largely seeking out creativity, beauty, joy, energy, strength, connection, even love. When we stand in front of a work of art, perhaps we’re even looking to connect with something bigger than ourselves. Corita Kent brought all of that to the museum and our community in powerful ways. Having her work on view here at the museum and seeing its deep transformative effect, I am drawn to reflect on how the power of art does spread out to a community and beyond the walls of a museum.

Because the children expect to find a place for themselves in the things we do in school, I knew I could expect authentic attempts at making meaning of the art in the “Constructing Identity” exhibition, and so I needed to focus on setting them up to be able to share the meanings they were making. My goal was to support the children to see each piece in the collection as a kind of long-distance offer of connection from one artist to another. I didn’t need to tell them how to connect with the art, how to find meaning in it — I just needed to ask them to, and I needed to give them some tools to do so.

Because the children expect to find a place for themselves in the things we do in school, I knew I could expect authentic attempts at making meaning of the art in the “Constructing Identity” exhibition, and so I needed to focus on setting them up to be able to share the meanings they were making. My goal was to support the children to see each piece in the collection as a kind of long-distance offer of connection from one artist to another. I didn’t need to tell them how to connect with the art, how to find meaning in it — I just needed to ask them to, and I needed to give them some tools to do so.

SUSAN HARRIS MACKAY is Director of Teaching and Learning at Portland Children’s Museum. In that role, she gives leadership to Opal School and the Museum Center for Learning, and works directly with children in the classroom. Opal School serves children ages 3-11 using inquiry-based approaches through the arts and sciences with a mission to strengthen education by provoking fresh ideas concerning environments where creativity, curiosity and the wonder of learning thrive. Along with her colleagues, Susan shares these fresh ideas through a professional development program for educators world-wide. Recent work includes chapters in Fostering Empathy Through Museums, and In the Spirit of the Studio, 2nd Edition, and a TEDx talk called, “School is For Learning to Live”. Connect with Susan and Opal School at opalschool.org.

SUSAN HARRIS MACKAY is Director of Teaching and Learning at Portland Children’s Museum. In that role, she gives leadership to Opal School and the Museum Center for Learning, and works directly with children in the classroom. Opal School serves children ages 3-11 using inquiry-based approaches through the arts and sciences with a mission to strengthen education by provoking fresh ideas concerning environments where creativity, curiosity and the wonder of learning thrive. Along with her colleagues, Susan shares these fresh ideas through a professional development program for educators world-wide. Recent work includes chapters in Fostering Empathy Through Museums, and In the Spirit of the Studio, 2nd Edition, and a TEDx talk called, “School is For Learning to Live”. Connect with Susan and Opal School at opalschool.org.

JESSICA RUHLE is Manager of Public Programs at the

JESSICA RUHLE is Manager of Public Programs at the