Written by Stephanie Downey

My career began at the intersection of museums and schools, and it will always be at the heart of why I do what I do. I discovered museum education while working as a program evaluator for the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS). I was doing that work because of my interest in equitable public education but discovered the wonders of object-based learning while evaluating a partnership between DCPS and the Smithsonian. Through that evaluation, I found connections among my personal and professional experiences and interests that I didn’t even know existed before. That project more than 20 years ago was a critical turning point that changed the course of my career and led me to museum evaluation. To this day, even though my interests in museums has grown beyond object-based learning, and my work ranges from exhibition evaluation to audience research, it is the work focused on museum school programs that lights me up.

The title of this post is a question that slowly came into focus for me in the last couple of weeks and sent me into a premature grieving for something I worry may never be the same again. In the middle of March, we watched museums close and school districts across the country send students home. I was alarmed but assumed, like most of us, the closures would be a relatively temporary situation. Yet as the pandemic has unfolded, it has become more and more clear that things in our country will not go back to the way they were before the virus, certainly not before a vaccine is widely available.

Through word-of-mouth, I’ve heard that school programs and field trips are very likely off the table for the rest of the 2020. And two weeks ago, Hyperallergic published this news—“MOMA Terminates All Museum Educator Contracts.” We learned that the Museum of Modern Art told museum educators in an email “it will be months, if not years, before we anticipate returning to budget and operations levels to require educator services.” Their projection of “months, if not years,” triggered a great deal of anxiety in me and among many others on social media.

As upsetting as it was to read those words from MoMA, I think most of us now realize there is not going to be a quick end to this. A recent article by Ed Yong in The Atlantic quoted Devi Sridhar, a public-health expert at the University of Edinburgh:

“Everyone wants to know when this will end. That’s not the right question. The right question is: How do we continue?”

Following from this expert’s words, the question for me isn’t “will museums keep working with schools during this time?” but instead, “how do museums continue working with schools throughout and beyond the pandemic?”

I believe strongly in the power of museum visits for school children, some of whom may never have been to a museum otherwise. There is something magical for students about entering a museum space surrounded by authentic artworks, objects, or artifacts they cannot see anywhere else. But it’s not just me and my bias for these kinds of programs. Over the years, numerous evaluation and research studies have examined the impact of museum programs on school children, and results show again and again that museum programs make a positive difference in the lives of students. Most recently, two large research studies—a national study of single-visit field trips to art museums by the National Art Education Association and the Association of Art Museum Directors in 2018 and study of field trips at Crystal Bridges in 2012—both showed that a visit to an art museum has a measurable effect on students’ creativity, empathy, and to some extent, critical thinking.

But, back to the “how” question. While it is preferable for students to engage with museums in museums, I advocate for museums not to wait the many months or years it may take for things to go back to “normal,” but instead to prioritize finding alternative ways to keep schools engaged with museums during this time.

I know many museum educators are already starting to do this, but I suspect it isn’t easy. While distance learning exists in museum education, it is certainly not the norm and presents a potentially steep learning curve for both museum educators and classroom teachers. Moreover, even when students go back to the classroom, schools may operate differently and be up against new challenges. The answer to this question of “how” may require a re-imagining of the relationship between museums and schools.

I wish I had the answers, but for now, I can only emphasize that, as a researcher and evaluator, I know the data tells us it would be a huge loss not to put resources toward sustaining and building museum-school relationships—first virtually, and eventually back onsite. I’m sure many of you have already started doing that reimagining. I would love to hear about it.

Featured Image: Students in front of Damian Aquiles’ Infinite Time, Infinite Memory, Infinite Destiny, 2003-2005 at the Orlando Museum of Art. Photo by Amanda Krantz, managing director at RK&A.

* * *

About the Author

STEPHANIE DOWNEY: Stephanie brings more than two decades of research and evaluation experience to her position as owner and director of RK&A, a museum consulting firm. She takes pleasure in working closely with museums and other informal learning organizations to help them make a difference in the lives of their audiences. Stephanie has undergraduate and graduate degrees in anthropology and ultimately is driven by her lifelong interest in how humans behave and make meaning. Prior to joining RK&A in 1999, she conducted educational research and program evaluation in public schools. Stephanie serves as treasurer on the board of the Museum Education Roundtable, frequently presents at professional association conferences like the American Alliance of Museums and the National Art Education Association, and regularly peer reviews manuscripts for the Journal of Museum Education and Curator. When not working, you can find Stephanie in the kitchen trying new recipes, cheering on her children in their various activities, and hiking trails along the Hudson River.

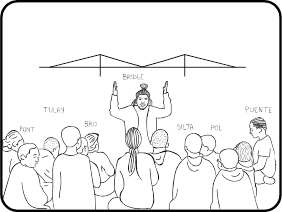

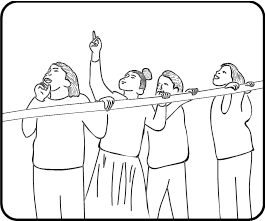

Because the children expect to find a place for themselves in the things we do in school, I knew I could expect authentic attempts at making meaning of the art in the “Constructing Identity” exhibition, and so I needed to focus on setting them up to be able to share the meanings they were making. My goal was to support the children to see each piece in the collection as a kind of long-distance offer of connection from one artist to another. I didn’t need to tell them how to connect with the art, how to find meaning in it — I just needed to ask them to, and I needed to give them some tools to do so.

Because the children expect to find a place for themselves in the things we do in school, I knew I could expect authentic attempts at making meaning of the art in the “Constructing Identity” exhibition, and so I needed to focus on setting them up to be able to share the meanings they were making. My goal was to support the children to see each piece in the collection as a kind of long-distance offer of connection from one artist to another. I didn’t need to tell them how to connect with the art, how to find meaning in it — I just needed to ask them to, and I needed to give them some tools to do so.

SUSAN HARRIS MACKAY is Director of Teaching and Learning at Portland Children’s Museum. In that role, she gives leadership to Opal School and the Museum Center for Learning, and works directly with children in the classroom. Opal School serves children ages 3-11 using inquiry-based approaches through the arts and sciences with a mission to strengthen education by provoking fresh ideas concerning environments where creativity, curiosity and the wonder of learning thrive. Along with her colleagues, Susan shares these fresh ideas through a professional development program for educators world-wide. Recent work includes chapters in Fostering Empathy Through Museums, and In the Spirit of the Studio, 2nd Edition, and a TEDx talk called, “School is For Learning to Live”. Connect with Susan and Opal School at opalschool.org.

SUSAN HARRIS MACKAY is Director of Teaching and Learning at Portland Children’s Museum. In that role, she gives leadership to Opal School and the Museum Center for Learning, and works directly with children in the classroom. Opal School serves children ages 3-11 using inquiry-based approaches through the arts and sciences with a mission to strengthen education by provoking fresh ideas concerning environments where creativity, curiosity and the wonder of learning thrive. Along with her colleagues, Susan shares these fresh ideas through a professional development program for educators world-wide. Recent work includes chapters in Fostering Empathy Through Museums, and In the Spirit of the Studio, 2nd Edition, and a TEDx talk called, “School is For Learning to Live”. Connect with Susan and Opal School at opalschool.org.

SARA EGAN is School Partnerships Manager at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Sara was recently named the Massachusetts Art Education Association’s 2017 Museum Art Educator of the Year. She teaches preK-12th grade students in the Museum and the classroom using Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), trains and coaches teachers in VTS, and conducts research on the impact of the Gardner’s School Partnership Program. Sara also manages the Gardner Museum’s paid Teens Behind the Scenes program, and is an adjunct professor of art at Simmons College. She has previously worked at the Andy Warhol Museum and Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh. Sara holds a BA from Vassar College and a Masters in Education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

SARA EGAN is School Partnerships Manager at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Sara was recently named the Massachusetts Art Education Association’s 2017 Museum Art Educator of the Year. She teaches preK-12th grade students in the Museum and the classroom using Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), trains and coaches teachers in VTS, and conducts research on the impact of the Gardner’s School Partnership Program. Sara also manages the Gardner Museum’s paid Teens Behind the Scenes program, and is an adjunct professor of art at Simmons College. She has previously worked at the Andy Warhol Museum and Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh. Sara holds a BA from Vassar College and a Masters in Education from the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

5.

5.  4.

4.  3.

3.  2.

2.  1.

1.